Family legacy creates contentious debate

College is not a pure meritocracy.

Many seniors carry the perception that legacy has a significant impact on one’s acceptance. And, for a handful of schools, this perception isn’t wrong. Nevertheless, the legacy system has both its advocates and critics, often creating a contentious debate about the nature and fairness of the practice.

Overall, legacy enrollment has decreased. In 1980, legacies made up 24 percent of Yale’s freshman class; in 2014, The New York Times reported that the figure had dropped to 13 percent.

Though the rates are declining, most selective schools– ranging from the Ivy League to selective public institutions– still take legacy into account.

Many admissions officers, according to The New York Times article by Evan Mandery, would “hasten to tell you that in a meritocracy, many legacies would get in anyway.”

Despite this, the benefits of legacy can be major. In fact, a study by Harvard researcher Michael Hurwitz showed that primary legacy applicants– referring to the parent who previously attended the college as an undergrad–had about a 45.1 percent better chance at getting into 30 elite colleges.

Many Staples students recognize the logic and reasoning behind this system.

Jackie Rhoads ’18, for instance, feels that colleges have a better idea about whether a child will enjoy the school, “because their family has fit into the academic environment before.”

An anonymous senior girl, who will be a third generation legacy at Cornell University in the fall, also believes that legacies help the entire school. “The money and time and support that families give to school really helps the school as a whole to become a better place of education,” she said.

However, there are schools and students alike who denounce the legacy system.

Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, has repeatedly spoken out against the practice of legacy, writing articles for The New York Times and publishing several books on the subject.

“Legacies do build communities,” he said, “but an exclusive one that is based on who your daddy is, rather than merit.”

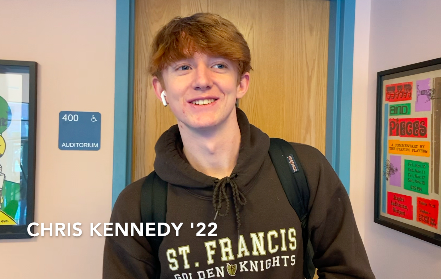

Given the controversy, some universities, like MIT and Caltech, do not factor legacy into their acceptances. In fact, Chris Peterson, a teacher at MIT, wrote in a blog post that legacy produces “a multi-generational lineage of educated elite,” with the primary goal of only gaining more money from alumni.

The claimed link between legacy and money raised the question about whether legacies actually do benefit schools financially. Winnemac Consulting, conducted a study from 1998 to 2007 and found that within the top 100 colleges, there was no significant statistical evidence proving that legacy preferences impact alumni donations.

Yet there are other studies that reach opposite conclusions. In fact, a study conducted at the Princeton’s Center for Economic Studies claimed that the chances that an alumni parent whose child goes to the school will donate is increased by 13 percent.

According to the Stanford magazine article “How They Got In,” the discrepancies between these findings may be linked to the difficulties schools face in quantifying legacy donations. College databases can see if an alum has stayed in contact with the school, but often cannot see specific donation amounts. This makes tracing the monetary connection with a legacy student difficult, causing schools to rely purely on the existence of the legacy itself.

But Katie Zhou ’14, a student at legacy-embracing Duke University, offered a different perspective.

“Colleges can say whatever they want about alumni relations and tradition. Legacy policies perpetuate the status quo and keep giving preference to already privileged families,” Zhou said.

Given that “multi-generational lineage” is, by a vast majority, white, there are accusations that legacy repeatedly favors the white elite.

“Legacies are part of a larger problem in which high-achieving low-income students are excluded from selective colleges and universities,” Kahlenberg said.

In fact, according to researchers from Duke University, underrepresented minorities made up only 6.7 percent of the legacy pool at 18 national schools.

However, it is also important to note that the same study found minorities only made up 12.5 percent of the applicant pool — a figure that may be reflective of a greater cultural issue.

Legacy continues to be a divisive college practice with both benefits and consequences for those who receive it.

“I know personally [being a legacy] has taken a lot away from the fact that I got in,” the anonymous senior girl admitted. “But in reality we are very strong applicants for the school as it is.”