By Amelia Brown ’18 Features Editor and Sophie Driscoll ’19 Opinions Editor

*Names have been changed

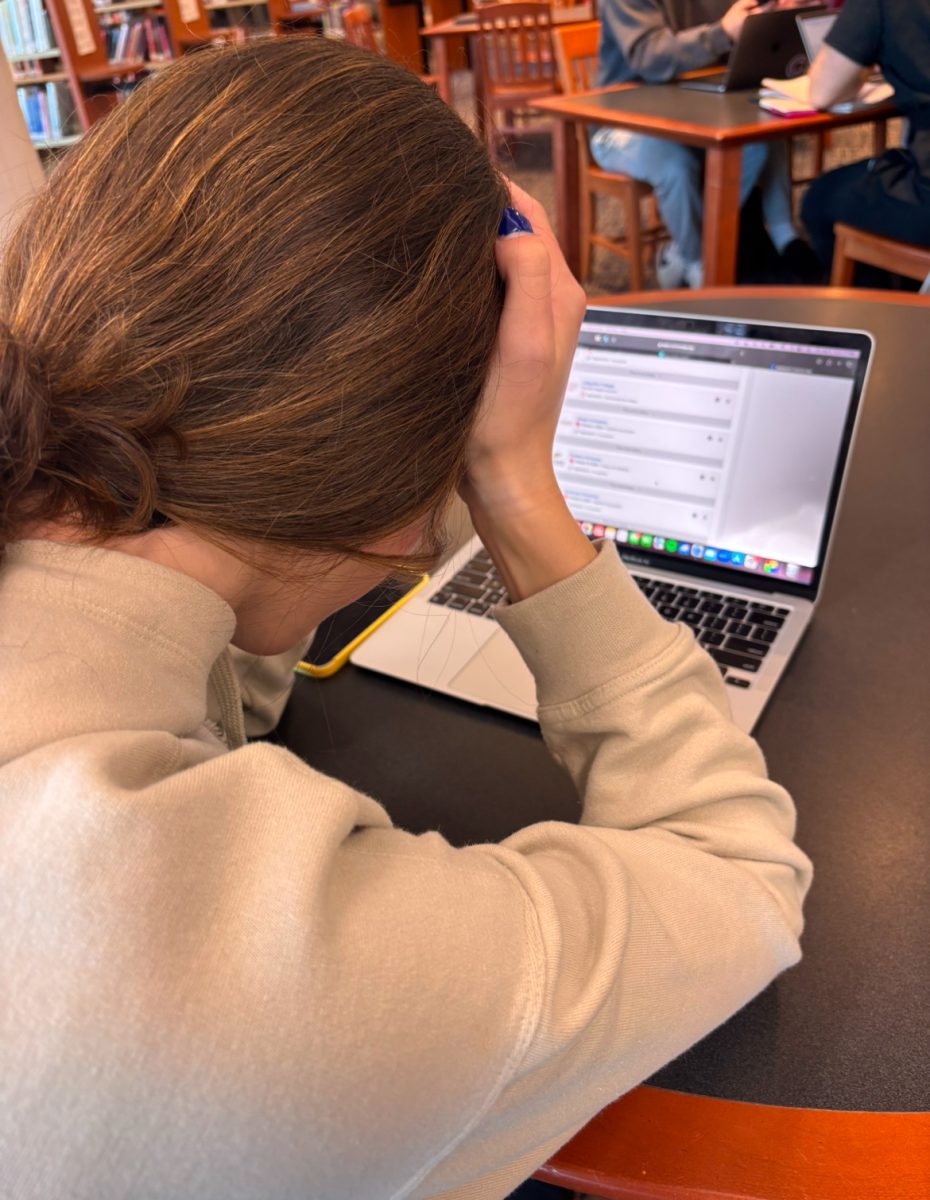

As Susan Smith* hurriedly grabbed her homework off the library printer, she noticed she had misspelled a word in her first sentence. Rushing back to the computer to fix the typo and reprint the paper before class, she mumbled an expression commonly used by high schoolers.

“Ugh, that was so retarded,” Smith said.

While students pride themselves on contributing to an accepting, positive school climate, students have reported the use of offensive, hurtful language. The r-word is just one example of language that marginalizes people.

“I’ve heard homophobic slurs from idiot guys who think it’s funny and think it’s cool,” Caroline Gray ’17 said. “It’s usually used in a scenario where it’s a negative thing. ‘That’s so gay,’ is [used as] a negative thing, even though [being gay] is not negative.”

According to a recent Inklings poll, four out of five students believe Staples is an accepting community, yet approximately 80 percent report having seen or heard some kind of marginalizing word at least on a weekly basis. Students report that they have heard their peers use language that marginalizes the LGBT+ community, people of color and others.

Staples administrators admit this marginalized language is used but state that it is not prevalent at Staples and is merely a reflection of a student’s youth and immaturity.

“I think you’re going to hear slurs of any kind anywhere you go, in any school system. I don’t know if it’s necessarily prevalent [at Staples],” Patrick Micinilio, 12th grade assistant principal, said

Richard Franzis, 11th grade assistant principal, agreed with Micinilio, and said Staples is a more tolerant place than most.

“I don’t know of a high school that is more tolerant of differences in kids than it is here. That being said, kids are still kids,” Franzis said. “They sometimes use language they shouldn’t use, and that’s a part of, I think, growing up and developing what you should and shouldn’t do and how you should interact with others.”

According to Dr. Alycia Dadd, school psychologist, learning how to interact appropriately with others is crucial, especially since marginalizing language is a widespread problem with a long and troubling history that should not be forgotten or ignored.

“Even though [marginalized language has] become commonplace, it doesn’t mean that we forget about who it was said about and how it was said or the context,” Dadd said. Dadd added that students use this marginalizing language “without understanding” it, rather than with malicious intentions, and that they often do not understand the serious implications of their words.

Case in point, when questioned about her use of the r-word, Smith admitted that she had no malicious intent. “I know it’s not a good word to use,” Smith admitted, “but my brothers said it all the time, so now it’s just a habit.”

Nevertheless, the lack of understanding and thought is insensitive and can be injurious. “A lot of time we hear kids say that it was just a joke,” Dadd said, “but that kind of numbs you to using language that otherwise you wouldn’t use.” According to Dadd, dismissing the use of marginalizing language as a joke is a “slippery slope.”

Looking to stop the slipping, Lily Dane ’17 is vice president of Best Buddies. She spends time after school hanging out with the club’s Buddies (students with cognitive or physical handicaps).

“I feel like a lot of kids at Staples might not have the experience of working with another student or peer who has disabilities,” she said. “When someone says [the r-word]…” Dane said, pausing contemplatively, before putting her hand on her heart, “it kind of hurts me a little bit because I know the Buddies, and they work so hard to accomplish just what seems simple to us.”

Whether students’ intentions in using marginalized language is to be funny or hurtful, Chris Fray, advisor of GSA, believes it shows an ignorance that must be addressed in order to promote change.

“Everybody is ignorant about something. We can’t bash people for being ignorant,” Fray said. “If we want to change a climate or change a behavior, it’s up to [us] to educate those people.”