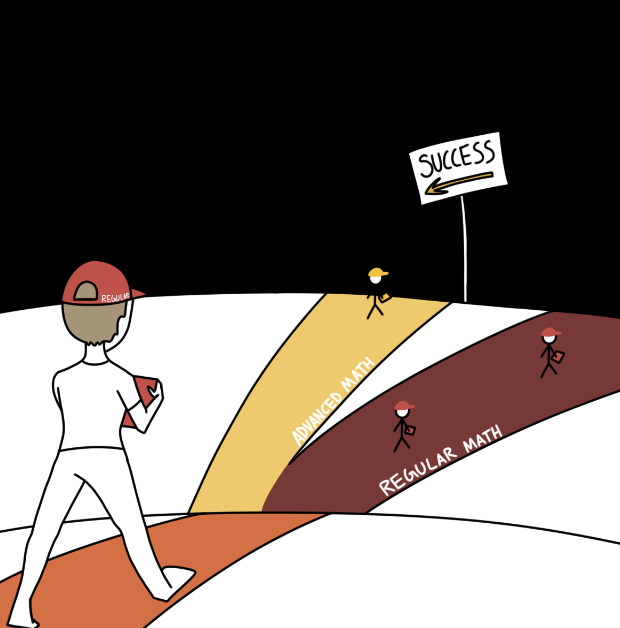

Unfair middle school math tracking restricts students in high school math placements

Graphic by Shivali Kanthan ’24

A student’s future success in school connected to whether a student is sent to regular or advanced math in fourth grade.

In high school, there is a lot of pressure to get good grades and take the “right” classes, especially at Staples. In an already competitive culture, I believe some Staples students are being unfairly left behind because of a math placement decision made by many fourth grade teachers. Although the system has been slightly changed recently, I am one of those students experiencing many inconveniences as a result of the old, unfair math tracking system.

In fourth grade, teachers determined whether their students will be placed in “high math” or “regular math” for fifth grade and based their decision on the student’s academic ability. Personally, I had very little interest in math when I was younger and seemed to be one of the easily distracted students. Therefore, I was placed in the regular math level and neither me or my parents gave it a second thought.

Upon entering sixth grade, the majority of students enrolled in either Math 6 or Math 6+, which, in student language, gets translated to “high math” or “low math.” Again, I didn’t worry or protest because we were told that there was nothing wrong with either level.

According to Math Department Chair Stefan Porco, they have recently changed this leveling slightly. Now, the class that used to be named “6+” is referred to as “6/7.” The 6/7 level covers sixth grade math and some 7th grade content, and makes it clearer to students and parents that the class advances students through math content more quickly. In contrast, math level 6 only covers the sixth grade material.

Porco confirmed that most students remain in their math trajectory through middle school, but students can move off of that path when deemed ready by having their parents sign a waiver and overriding the recommendation.

However, when I was in middle school, the differences between the levels were not made so clear. As a result, students like me who had only taken “low math” courses were surprised to find that we were at least one whole year behind our peers who had taken “high math” classes throughout middle school.

The students who were placed in higher middle school math levels completed Algebra I in eighth grade, and either enrolled in high school geometry (a math level that is one whole year ahead of Algebra I) or Algebra II if the students were identified as “gifted” through the formal identification process.

In contrast, the students who remained in the lower math levels during middle school enroll in Algebra I as a freshman at Staples.

Porco defended the tracking process for math by pointing out that unless a student would really like to excel in math, there is no “correct” place to be, but rather that the student is at a level appropriate for them.

However, while I can understand that point, considering that the only time a student can move levels is in 6th or 7th grade, my question is: How can a young student possibly know what they would like to excel in at such a young age? And how can anyone know whether their goals and desires for math would ever change?

For instance, Abby Epstein ’25 is a student who was enrolled in the Coleytown Middle School “low” math and found herself at a disadvantage once she enrolled at Staples. Epstein says she doesn’t know exactly what she wants to do in her life, but she wants the option and doesn’t want any opportunities limited for her as she gets closer to graduating.

So, in order to “catch up” to her “high” math peers, she has had to take two math classes simultaneously. As you can probably imagine, handling two math classes at once is difficult.

“Sometimes I mix up the material and get confused when I do my homework,” Epstein admits.

In my view, it would be like learning two different languages at the same time.

Taking two math classes simultaneously is not the only inconvenient way for students enrolled in “low” math middle school classes to catch up. They can also opt to give up part of their summer and enroll in summer math class.

Specifically, students looking to catch up can take an optional summer geometry course. This class takes 4-5 weeks, and allows them to start sophomore year in Algebra II. Staples guidance counselor Thomas Brown said that about 20 people have enrolled in the course each year for the past three summers.

But these options for kids coming from “low” math ignore the real issue: why were “low” math kids having to take extra classes at all?

Again, when I was in middle school, it was the math department’s stance that regular math and “high” math classes were assigned to each student specifically towards their ability; this was the message being delivered to parents and students.

The truth was that “low” and “high” math was never equal. They did not equally prepare students for high school math and there was more than just pacing that was different.

Teachers want students to remember that not everyone’s abilities are the same and each individual student has their own strengths. But in a competitive environment like Staples high school, it is important that classes be described accurately, and students and parents–not elementary school teachers– have more of a say when it comes to determining which math level is best for them.

It is wrong for a student’s math future to be practically engraved in stone by their fourth-grade teacher. It is wrong to assume a child’s interest or ability in math cannot or will not change over time. And it is especially wrong that a lower-level math program does not provide its students with enough instruction and opportunity to give them a hope of ever changing their math tracks later in their school careers.

Unfortunately, kids like me are continuing to deal with the consequences, but at least future generations will not face the exact same trials as we have.