“Cancel culture” is not the punishment everyone thinks it is

Rachel Greenberg ’22 and Katie Simons ’22

The massive outcry against “cancel culture” provides us with an opportunity for introspection. It is a reminder to identify our own values and goals and to understand that they are bigger than fleeting public interest.

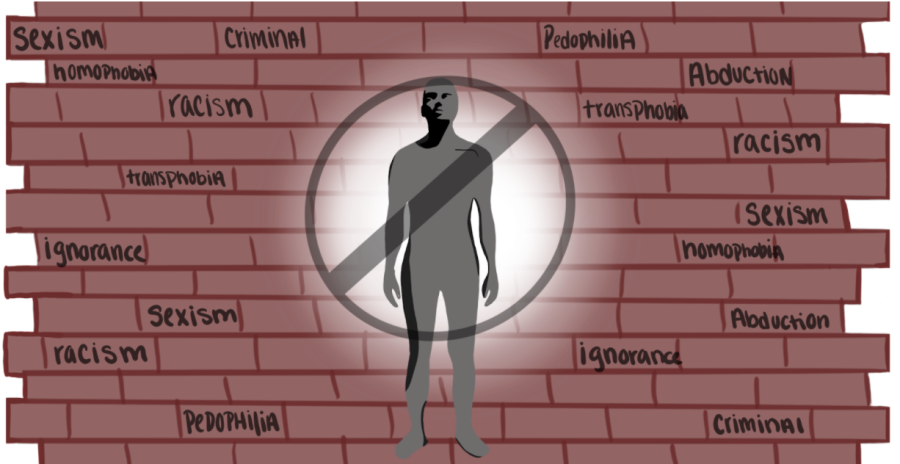

The list of supposedly “canceled” figures is extensive and diverse. Real people; fictional characters, companies and corporations, even ideologies––including “cancel culture” itself in a paradoxical and oxymoronic movement to “cancel cancel culture”––have all been targeted by the vindictive judgment of a “cancel culture” mob.

“Cancel culture” describes the phenomenon of public shaming and ostracization in response to perceived transgressions. It is typically seen as seeking to remove someone or something from a place of esteem or from the public view entirely.

For something that began mostly in the online sphere of anonymous Twitter accounts and obscure trending hashtags, “cancel culture” as a topic of public concern has transcended its humble beginnings enough to become a major part of political platforms.

Pundits, congresspeople and presidents alike have all voiced their concern for what they deem a worrying trend that threatens sacrosanct pillars of a just society. “Cancel culture,” in the eyes of many, is a malevolent force that threatens every day to stifle free expression and choke dissent.

Yet, for all of the outcry, all of the noise, there seems very few real consequences of “cancel culture.” Popular youtubers like James Charles, Jeffree Star and Shane Dawson, targeted by “cancel culture” for sexually predatory behavior, racism and even bestiality, continue to garner millions of views on their videos, sell their products and sustain themselves financially. Jeffree Star’s most recent video, for example, had surpassed a million views less than a week after being posted. If anything, the public outcry has brought them more recognition in circles beyond their own niche internet communities. There is, in the online sphere at least, no such thing as bad press

Even for “cancel culture’s” more mainstream “victims,” consequences are difficult to come by. J.K. Rowling, for example, has not exactly become the pariah many like to think she has. Even with her extremely transphobic rhetoric that has included the same bigoted talking points we all know and love,––featuring such classics as “the horrors of men in women’s bathrooms”––she continues to be one of the most successful authors of all time.

Her most recent book, “The Christmas Pig,” from October of 2021–– well after she revealed herself to be a raving and unapologetic transphobe––still made it to the top of the UK’s best sellers list, selling twice the amount as the book holding the second spot.

This lack of ramification is even more obvious in the case of “canceled” corporations. Businesses like Chick-Fil-A and Hobby Lobby have both been on the receiving end of digital disapprobation for actions such as donating significantly to homophobic organizations, fighting to withold birth control from employees and even smuggling biblical artifacts from Iraq.

Regardless of this extensive and somewhat surreal catalog of offenses, both companies continue to profit and expand, as well as the individuals at their helm who are responsible for their misdeeds.

The other problem is that “cancel culture” is frequently the term employed to describe reactions to publicized behavior that, quite literally, is illegal. Public castigation in reaction to that behavior is not “cancelation;” it is a warranted response to actions that violate moral and legal codes.

An article from CNN cites R. Kelly as among an annual roundup of “cancel culture” targets, which, frankly, is absurd. R. Kelly has not been canceled. He was quite literally found guilty of crimes that included kidnapping, sex trafficking and producing child pornography. I reject entirely any assertion that identifies him as a victim of a woke mob of liberal keyboard warriors.

Despite this, he continues to receive public support. His Spotify artist page, for example, as of February 2022, attributes to him over 4,000,000 monthly listeners, nevermind the fact that his discography is still hosted on Spotify at all. If R. Kelly represents an extreme case of “cancel culture”, the consequences, as far as the withdrawal of monetary support from the public, are non-existent.

The internet, as a collective, does not have the will nor the attention span to dedicate any real effort towards suppressing someone or something for longer than about a week. Furthermore, “cancel culture” is not new. People have long been emboldened by popular support to condemn things they find distasteful, however minor those things may seem to others, since the dawn of time. The internet has served only to amplify conversations that were already being had.

The major issue with “cancel culture” has less to do with the phenomenon itself than it does with the way we talk about it. Discussions about the unfairness of an unforgiving group of internet users or even sectors of society have begun to obscure the problems we sought to address in the first place. Complaining loudly and often about how J.K. Rowling has been victimized by the internet has gotten, and will continue to get, in the way of real conversations about transgender rights and liberation; asserting that Shane Dawson has been treated unfairly can overshadow discussions about racial charicutures in entertainment; and the list goes on.

Politicians, especially, are in a position where complaining about a woke mob can either get in the way of dealing with the issues they were elected to handle or can provide them with a way to escape blame for some offensive act they have committed. Addressing a transitory, concentrated reaction rather than the events that led to it has never been the most effective way of going about anything. Yet, that is where these discussions about “cancel culture” often take us.

“Cancel culture” is not and should not be treated as the scourge of modernity. It is something of an illusory abstraction that appeals to base desires to identify with victimhood rather than wrongdoing. In endorsing the idea of a vaguely evil digital force that could shatter the pillars of society, we lose sight of the things with the real potential to disrupt progress towards societal justice, of which there is no shortage; seeking to change something that exists only as white noise in cyberspace is a waste of time.

If nothing else, the massive outcry against “cancel culture” provides us with an opportunity for introspection. It is a reminder to identify our own values and goals and to understand that they are bigger than fleeting public interest. To subvert the new problems created by regard for “cancel culture,” then, we need only refocus and work with even more ardor and conviction toward the things of real consequence. Now is a better time than ever to recommit ourselves to doing all that we can to surmount the more material issues in our society and it would be a mistake not to do so.

Judson • Aug 10, 2022 at 5:47 pm

I just wanted to say I enjoyed this article. I think it is a very rational and thoughtful way to look at “cancel culture“. It does get difficult to tell the difference between a true threat and a cultural meme.

But, I agree. I feel the whole “cancel culture “concept has been used by many a political platform to create an enemy. By creating this enemy and now adds fuel to those who seek out this enemy. It’s definitely something that causes a greater divide as yet another in-group out-group is created and fostered.

I wanted to compliment you on this article. Very thought provoking and very thoughtful and rational.

Tselin • Jul 28, 2022 at 3:04 am

Is it illegal where the majority of humanity resides? The west is no longer able to claim that.