Impending holidays demand vigilant expenditure

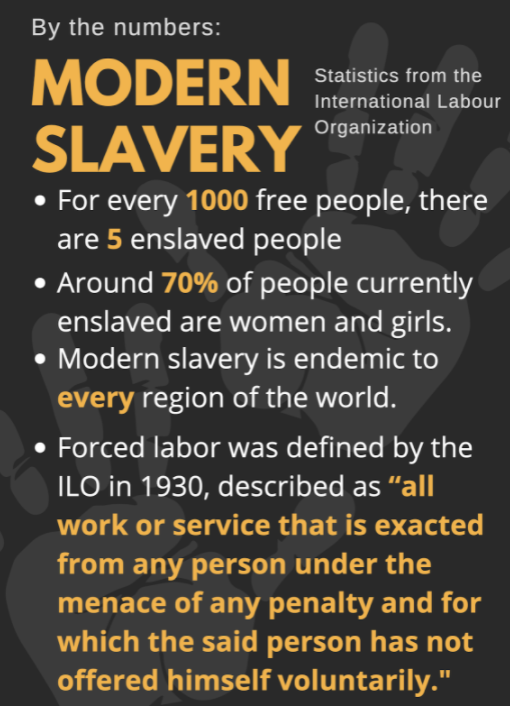

Working conditions are just one of many considerations to make when shopping this holiday season. Many companies benefit from modern slavery or dangerous and unjust working conditions somewhere in the supply chain and should thus be avoided.

As a rough estimate, there are 40 slaves working for me. That is a horrifying statement to make; it is a horrifying fact. In all likelihood, there is a similar number working for you.

As per slaveryfootprint.org, there are 27 million people suffering under modern slavery, a practice supported every time someone buys certain brands of shirt, electronic or food. You can determine roughly how many work for you through their slavery footprint survey. As gift-giving holidays draw nearer, it is our obligation, not only to our own moral codes but to other people, to demand the best from the companies we support.

There are wide-ranging implications of any monetary transaction, as should perhaps be expected in a world fueled by money, and that includes supporting practices of injustice. Beyond modern slavery, there are people maltreated and underpaid, environmental impacts and company politics to contend with when disseminating the morality of buying any particular good.

“40” is a neat number. It is an easy, apathetic calculation that conveys more about the distance between me and human suffering than about the people it represents: 40 people suffering under slavery at this exact moment in time, 40 people who will continue suffering under slavery in the moments afterwards as well. To think, to any degree, that we could begin to understand the ugly underbelly of those numbers, the depth of human suffering they represent is equal parts audacious and ignorant.

Thankfully, one is not required to fully grasp the complexities of tragedy to wish it did not exist and to feel acute distress at the prospect of participating in it.

Most people are not in the position to be investing in organic cotton or fair trade coffee beans. However, in Westport, Connecticut, where, according to a Bloomberg article from 2020, the average household income is over $300,000 a year, most residents here can afford to be a bit more particular about the goods they consume.

It is true that this is an issue that extends far beyond the individual. Injustice is supported by a complicated economic and political infrastructure that no single purchase has or will fracture. It is a systemic problem that warrants systemic remedy.

Nevertheless, this is not a commentary on capitalism and free markets. I will not appeal to anyone’s preexisting affection for or disillusionment with economic constructs and the abstract terms that accompany them. It is an affirmation of the basic humanity required to wish that others be treated fairly; it is my refusal to continue contributing to the suffering and cyclical injustice of millions of people who are just like me. They are just like you, too.

I would not deny that it is tedious and difficult to evaluate the ethics of each company you purchase from. Despite this, there is no shortage of places to start. Better World Shopper is one. It is “a comprehensive database of over 2000 companies and utilizes 76 reliable sources of data so that the public can hold companies accountable in a practical way,” and can be searched prior to making purchases to ensure one is making the best choice possible.

In want of systemic change and education therein, the UN’s International Labor Organization, a branch that, according to its website, seeks “to set labour standards, develop policies and devise programmes promoting decent work for all” maintains a database of global labor legislation. The United States has a profile that can be found here.

Despite the magnitude of the problem, the resources for a proactive individual response are never far. More than anything, at the heart of the issue, it is a problem that demands compassion, humanity and a willingness to embrace the discomfort of awareness.