Stop trivializing mental illnesses; it invalidates those who struggle

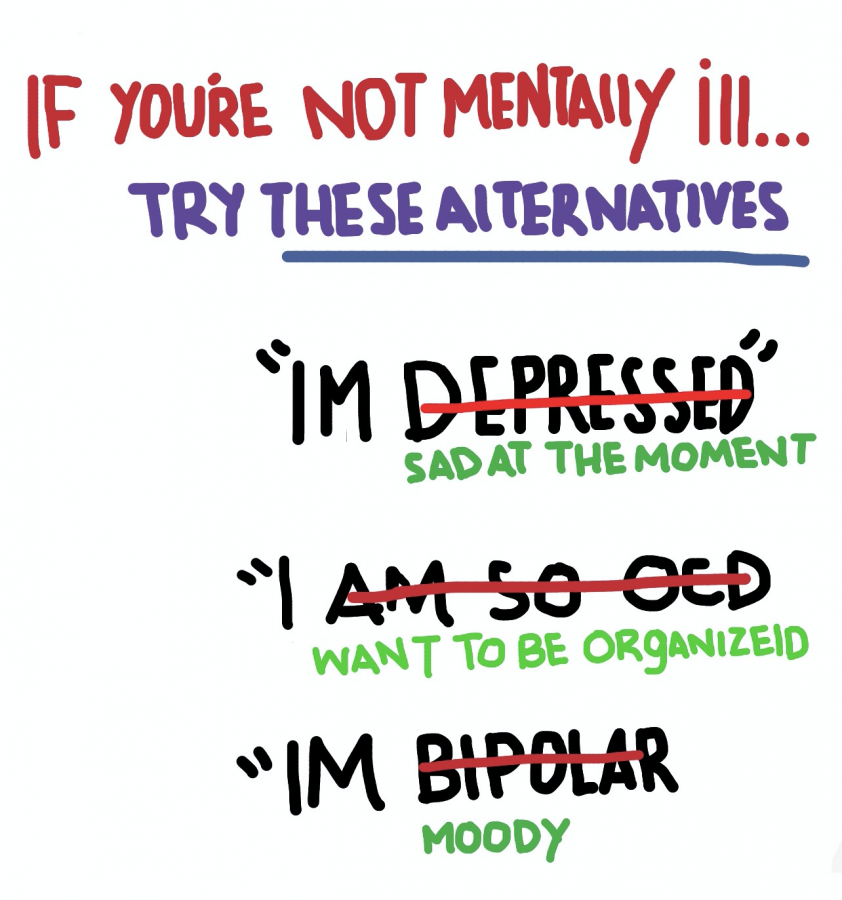

Graphic by Valerie Dreyfuss ’22

“Using terms such as ‘depressed’ or ‘ocd’ when not diagnosed with these illnesses can be both triggering and invalidating of those really are.”

Yesterday, I was in a public library and overheard a girl who was studying for a math test. “I am so nervous for this test,” she laughed, “I’m having a panic attack.” Although I understood what she meant, her words were a bit of a gutpunch. This term is used all the time, in similar lighthearted ways.

As a person who has experienced panic attacks and anxiety disorder , it was jarring to hear her use that term in such a joking way. However, I don’t blame her; many people unknowingly trivialize mental illnesses by using words like panic attack to express common everyday emotions.

When people use this terminology, they simply don’t understand the negative impact they’re having to those who grapple with mental illness. They may not know that almost 50% of teens cope with anxiety and other mental illnesses. Or that those “anxiety attacks” they joke about are not just feelings of nervousness. They may not know that illnesses like anxiety affect people every single day, and not just before a test in school.

Many Staples students grapple with mental illness. I myself have experienced panic attacks, and can attest that they are nothing like the common nervousness we feel before a big test. This is why I understand how damaging it is to talk about mental illness in a way that trivializes the experiences of those coping with them.

People use this language without even thinking about it; saying you’re “depressed” when you’re sad, “ocd” when you’re organized, or “bipolar” when you’re moody. Using these terms downplay the seriousness of mental illness, perpetuating confusion about the line between normal emotional unrest and conditions that require professional help.

The misuse of these words also negates the experiences of those who are actually suffering. When people jokingly or unthinkingly use these labels and simply “deal with it”, they inadvertently make those who do struggle feel invalidated and think they don’t need help either. If someone who has anxiety does not seek help for this reason, it will only worsen their condition and even sometimes put both them and their mind in danger.

The overall stigma and misconceptions about mental illnesses have never been more prevalent in today’s society, and loose labeling only makes them worse. Not for our sake, but for the sake of those who are truly struggling, we must recognize the difference between an emotion and a diagnosable illness.

Paper Opinions Editor Valerie Dreyfuss ’22 is an Inklings veteran, kind of by accident. After taking Intro to Journalism without really knowing what...