Columbus Day should prompt sober reflection, not celebration

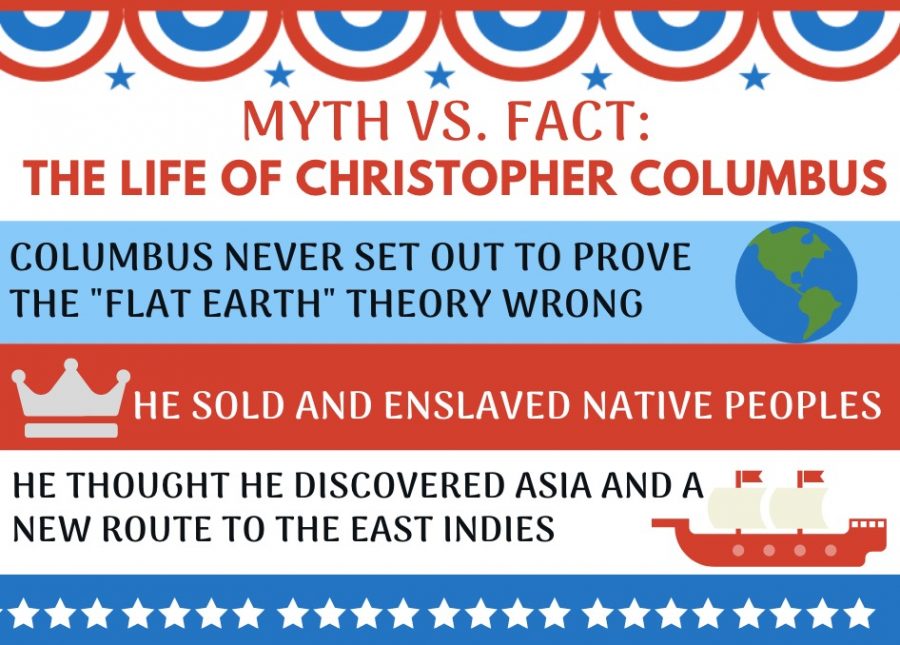

Infographic by Kaela Dockray '20

The controversies surrounding Christopher Columbus render the holiday named in his honor a polarizing issue.

Christopher Columbus is our national contradiction: a man simultaneously lauded for his determined spirit of exploration and reviled for unabashed imperialism. His status of aberration, however, makes the holiday named in his honor a polarizing topic among those who disagree on his connotation in history.

Columbus Day should not be a celebration of adventurism—to restrict his legacy to such a word is nothing but ignorant glorification of history. I think it unwise, however, to rid ourselves of the holiday entirely.

Over 500 years ago, Columbus “discovered” the New World on Oct. 12, ushering in the Age of Exploration and making the connection between Europe and the Americas. Since 1934, this nation has observed an official holiday in his name on the second Monday of October, though several states in many cities have never marked the holiday or have chosen to replace it with versions of “Indigenous Peoples Day,” to acknowledge previous ongoing struggles of native people who needed no discovering.

Admittedly, of course, the holiday is problematic. However, I believe Christopher Columbus Day should not be eliminated from the calendar. Rather, our country’s most inconsistently-observed holiday affords us an opportunity to examine inconsistency itself. History is an instructive tool and understanding the challenges at present.

Columbus Day should be one of balanced reflection, considering Columbus’ achievements in context of his failures.

There are those who argue the holiday honors the history of immigration, not the explorer. Certainly, a universal moral imperative makes it impossible to find Columbus’ habit of violence, enslavement, forced religious conversion and the introduction of deadly disease compatible with prevailing principles of our time. Personally, I find his penchant for beheading, mutilation and other acts of the like to be abhorrent. The misery and degradation that plagued the New World after the arrival of colonial powers should not be overlooked or dismissed. As such, the holiday should not be chiefly commemorative.

The continuation of the holiday should not signify blind acceptance of the actions of former societies, but we should reflect upon such values. It is impossible to separate Columbus Day from its shroud of oppression completely. No country exists without blemishes—least of all ours—but we would do well not to merely forget them. Five-hundred-years of history has not been sufficient to clean the stains of imperialism, and I doubt 500 more years will do much more in that regard. Columbus Day, then, should be an opportunity to reflect on the horrors of historical experience and the evolution of society from the past.

The continued observance of Columbus Day should not signify acceptance of racist exploitative actions of former societies, but should inspire us to honor the contributions of an intermixed heritage. In this age of border walls and missions to Mars, Columbus Day should remind us all of the errors of the past and the obligations of the future.