Chanel Miller’s memoir on surviving sexual assault highlights oversight of high schools to teach consent

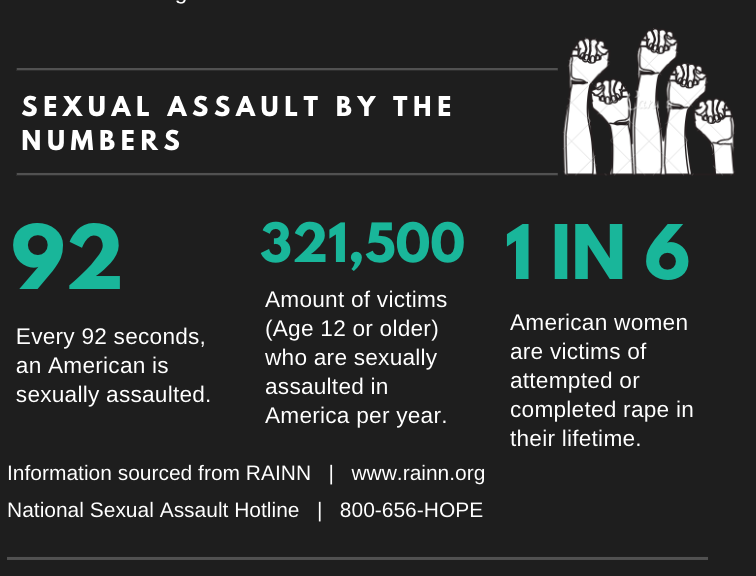

Infographic by Rachel Suggs ’21

Statistics from RAINN and the National Sexual Assault Hotline prove the commonality of sexual assault.

Chanel Miller, survivor of a highly publicised 2015 sexual assault, revealed her identity through the Sept. 24 publication of her memoir, “Know My Name,” after four years of anonymity in the media. By doing so, she not only forever changed the way we view sexual assault, but she exposed the weakness of high school sexual education curriculums to neglect education on consent. Staples must properly teach students about consent in Health class, as it is a life skill that students need for college life and beyond.

Chanel Miller was raped outside of a fraternity party on the campus of Stanford University, according to a 2019 NPR article. Miller’s college rape was not rare by any stretch of the imagination; it is one example of the epidemic of rape on school campuses. According to RAINN, 23.1% of undergraduate females and 5.4% of undergraduate males experience rape or sexual assault every year, and 10% of high school students were sexually assaulted in 2017, according to a 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey by the Center for Disease Control.

We are misguidedly treating college rape as though it can only be mitigated through reactive, punitive measures. But we must start preventing rape culture proactively, by understanding that college students were once teenagers who should have been taught consent in high school.

Although the state of Connecticut does not mandate any sexual health education, according to state department of education, Staples has taught sexual education in the form of contraceptives.

But I personally have no memory of a specific conversation about consent in Health class. It might have been tied into a unit on contraceptives or mentioned as an off-the-cuff remark by a teacher before the bell rang, but we never discussed the different kinds of consent, such as verbal and non-verbal, or the importance of it.

This is especially ironic because the Staples website specifically claims that Staples “is dedicated to the lifelong goal” of health.

“While enrolled in the Staples High School Health and Physical Education programs, students will be introduced and exposed to activities that promote health and physical literacy, lifelong wellness and encourage lifetime activity,” the website states. “Our goal as a department is for students to become competent in all activities; and proficient in the activities they choose to pursue through high school and beyond.”

Consent is a form of health and physical literacy. Students need to know what consent looks like, and how consent can be withdrawn, to exist in this world as college students and global citizens. If Staples can take its own initiative to teach contraceptives without a state requirement to do so, surely it can teach the foundation of sexual consent.

Moreover, just because Staples does a decent job training its students to be altruistic citizens, stressing the importance of a global community in its classroom curriculums, does not guarantee that students will not grow up to be perpetrators of sexual assault.

“The friendly guy who helps you move and assists senior citizens in the pool is the same guy who assaulted me,” Miller writes in her memoir. “One person can be capable of both. Society often fails to wrap its head around the fact that these truths often coexist, they are not mutually exclusive. Bad qualities can hide inside a good person.”

Teaching kindness as a school does not make up for the lack of consent education. Emphasizing compassion is not enough to truly prevent potential sexual violence. We need to have a specific Health class devoted to a discussion on consent.

High school is supposed to not only teach its students math formulas or Shakespeare soliloquies, but it must also equip teenagers to take on adult life. By failing to properly teach consent in sexual education classes, Staples is failing its students. Male students have not learned what consent is, and female students have not learned how to give or withdraw consent.

If the Staples health department really wants to promote life-long physical literacy, it needs to begin teaching consent as a lesson of its own focus, so that rape culture is prevented early on, and no other college student like Chanel Miller has to ever endure another sexual assault.