I was on a train going towards Grand Central last week when I saw two dark- skinned men sitting right behind the car door. They were probably in their 50s, but their old, tattered sweatpants and rugged, uneven faces turned them into 60. One of them had a beard (though I doubt it was on purpose) and the other had the early beginnings of one. Looking further down, there was a plastic foot jutting out of the shaven man’s right leg opening. The words imprinted on his crew neck had faded from the bold shape that probably once defined him, as well. The letters spelled out “Support Vietnam Veterans.”

The two men were holding each other with their hands clasped. When a tall guy wearing a Yankees cap moved his eyes towards them, the bearded man yelled “What the f*** are you looking at?” Then the doors opened and the tall guy walked out.

* * * * *

As I looked at these men, I started thinking about the world outside mine for the first time in a long time; I started to see the great enigma of human relationships. So many of the people on that train had probably already summed up each other’s life stories — my life story. If every lie formed a physical object, nearly every person on that train would be sitting in their own cubicle.

And, in many instances, this becomes a good way to define Westport: as a cubicle, or, using the phrase more commonly alluded to, as a bubble. Everyone, including me, tends to avoid thinking about people who are inconveniently different than they; we describe ourselves as progressives but then assume the guy begging for money on the train platform is just a junkie or lost cause.

And this sort of logic makes sense – Mother Teresa wouldn’t have the emotional wherewithal to ask every immobile person watching the black-suited world walk by, “How was your day?”

Similarly, kids my age will compartmentalize others into neat, simple descriptions, which can be used to justify one’s empathy or lack thereof: this kid from ____ has no intention of going to college so he’s going nowhere in life; that girl is a Republican so she must not care about poor people.

This isn’t to say that we don’t develop these predeterminations around other Westporters – because we do. God knows middle school would have been better if people thought I was athletic. But the problem becomes so much worse when many of the people around you have, or act like they have, the same general beliefs and background and outlook on life as you have. And there’s no reason to fault someone for this; these are the people who are close to us – they are the people we understand. And understanding is fear’s greatest enemy.

But when we get too comfortable with the things we know, when one word descriptions of others – whether they be from Texas or Trumbull – are used as excuses for not venturing too far out of one’s own insulated group of acquaintances, so much is lost. Empathy becomes unnecessary, ideas become closed-minded, and our politics become immovably righteous and divided.

Though Mark Zuckerburg would argue the contrary, the Internet isn’t helping much either; there’s no reason to truly understand someone else when their personality is summed up within a few status updates and profile pictures. Ideas straying too far from your point of view are swallowed by the filter called Google; the search results at the top of the webpage are based on the interests you divulged in previously visiting a certain website. So when I search News or Rock ‘n Roll, I will never have to listen to the detested Bill O’Reilly or Aerosmith. I will never have to hear the devil’s advocate.

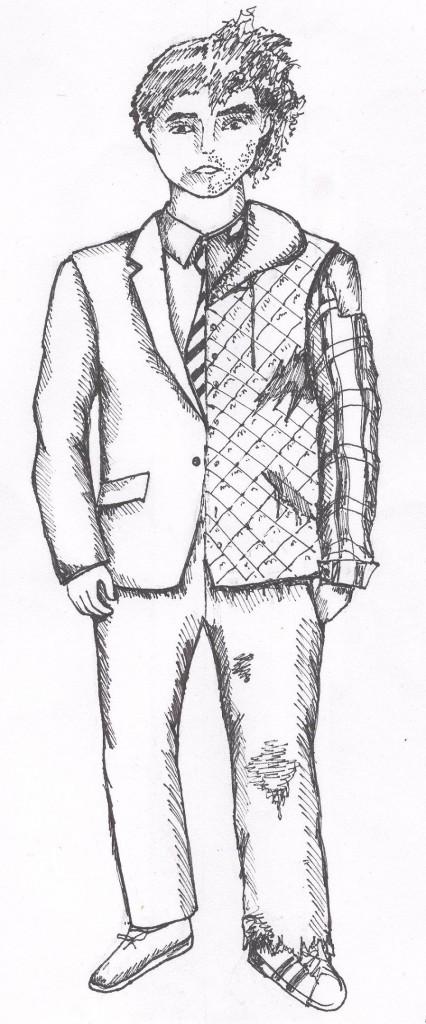

Everybody has a story to tell about themselves with chapters describing ups and downs, pain and love; the same emotion are repressed in a man’s chest whether it is covered by a suit and tie or torn crew neck. It is taken for granted in a child’s eyes that a snapback or Snuggy doesn’t define someone, but social pressure and TV and billboards depicting unrealistically handsome models slowly convince us otherwise.

A lot of growing up is about rediscovering a tolerance and empathy that was once intrinsic; it is about learning to learn from people whose styles or ideas may come off as outlandish or unpopular. It’s about stepping outside of your own bubble.

Though it may be buried deep within our self- conscious, we are all capable of this open-mindedness. It just requires you to admit that you’re as imperfect as anyone else.

* * * * *

In the midst of my reflections, a grey haired gentleman wearing a sleek navy blue suit and gripping a leather suitcase walked through the door. He then opened his body towards the two open seats across from the crippled man and bearded man who’d told at least three passengers to go “f*** themselves” by now. After dusting off the faded red leather seat, he sat down. I stared from afar and waited for him to get cussed out for his bewildered glance. He was staring at them like a kid seeing Ronald McDonald for the first time.

It took five seconds for the bearded man to ask, “What the f*** are you looking at?”

“His leg,” responded the suited man. “How did he lose it? I was drafted in ’73 with all my brothers, but I was the only one not to go. I had flat feet.”

“Well thank your ugly feet for saving your legs.”

The half- shaven man with the prosthetic leg sat up as straight as he could and, for a split second, divulged a half, broken- toothed grin.

Then, with somber eyes and a raspy voice, he whispered, “Thank you.”