No one can predict when something bad will happen. A month ago today, just a few towns over, 26 people were killed: six teachers and 20 children. It would have been impossible for anyone to anticipate such an event.

Here at Staples, that Friday came and went. It was a confusing day, followed by an emotional weekend, during which teachers heard nothing from the school about what to do on Monday.

Principal Dodig did make an as-promised speech during the usual morning announcements and led a moment of silence.

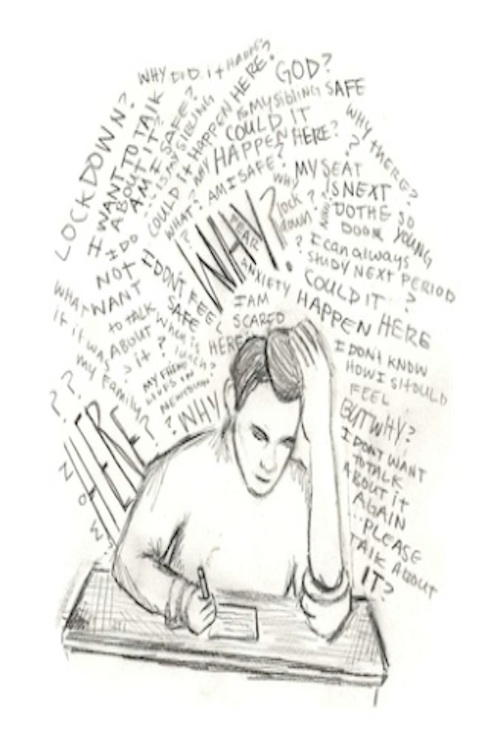

But students’ thoughts continued to race.

Am I safe here?

Where would I hide?

This could have been us.

Students’ concerns correlated neither with the worksheets on their desks nor with the writing on the whiteboard. The shooting eclipsed anything and everything academic that Monday. Things that would have been important just a few days before suddenly became unimportant.

Instead of calculating derivatives, conjugating verbs, or crafting in-class essays, many students needed to make sense of the Friday before.

Students wanted to know what actually happened at Sandy Hook. They wanted to learn our school’s emergency plans. They wanted to believe that they were safe. They wanted to hear if anyone knew anyone who died. They wanted to understand the motivation of the killer– why?

Deciding that there would be “no talk of what happened,” as some students reported teachers announced, or simply ignoring what was on everyone’s mind, did not help.

To be fair, administrators are people, too. As one said, they also were in shock the weekend after the shooting. It wasn’t only students and teachers who died in Newtown; a principal died, too.

But with no guidance from the school, teachers were on their own. They had no choice but to default to their own coping mechanisms.

Some teachers dealt with it Monday and even Tuesday by letting their students ask questions and talk. Some teachers told their own stories. Some designed whole lesson plans circling around topics like evil and hope or gun control and the Constitution. It was comforting. Other teachers moved swiftly

into their normal Monday lesson plans, simply because they didn’t know what else to do or because that felt right to them. And maybe they really thought they were helping us. Can we blame them?

Teachers themselves were unraveling. Some of the discussions in their offices and at their lunch tables were unnerving, sad, and deep. They had questions, too.

How does a lockdown work, anyway?

Would I die for my students?

Are kids still talking about it?

What were teachers supposed to say to their students when they were struggling with what to say to themselves?

They would have read crafted scripts from the administration. They would have participated in a school assembly or homeroom. They would have drilled lockdowns. They would have done anything.

An elementary school shooting is rare. Unfortunately, crises are not. There are other hardships and moments of anguish that also call for a thoughtful, cohesive plan to respond to the needs of the entire community.

No one can ever be prepared for an event like the shooting, or any other tragedy.

What we can do, though, is prepare for the aftermath.