And you thought the movie “2012” was a flop.

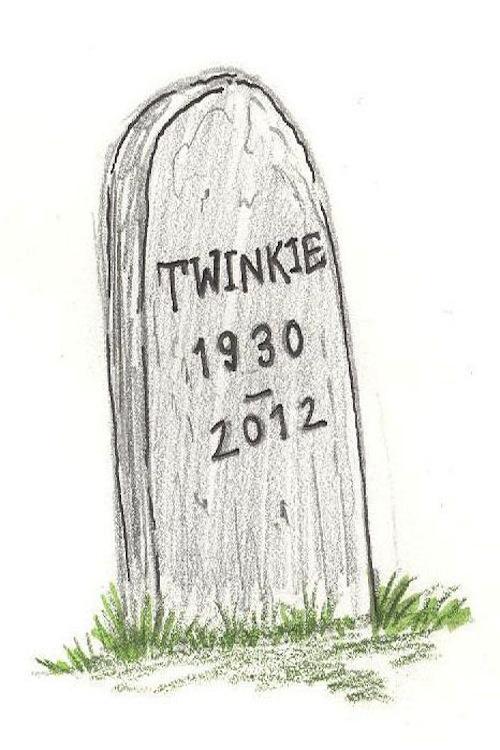

As most Americans raced home from school and work on the afternoon of Friday, Dec. 21, eager to begin their holiday breaks, fire and brimstone did not rain down from the heavens, nor did a tremendous cataclysm ravage the planet. Earth did not turn into a real-life “Lost,” “Revolution,” “The Walking Dead,” or even “Jersey Shore.” A lone survivor did not wake up on Dec. 22 to find a charred landscape populated only by cockroaches and Twinkies. We even had a picturesque white Christmas, the opposite of apocalyptic mayhem. The only failed prediction less surprising was Jets coach Rex Ryan’s annual Super Bowl guarantee.

To the vast majority of human beings intellectually capable of logic and reason, this result was unsurprising. That’s because the most commonly-cited evidence of an apocalypse, the Maya calendar, never actually says the world will end.

After centuries of being best known for their bizarre rectangular hieroglyphs, slaughter at the hands of imperialistic Spaniards, and Chichen Itza—a haven for hipster pyramid enthusiasts who find Egypt too mainstream—the Maya came to prominence a few years ago when people with too much time and not enough knowledge of anthropology stumbled upon their calendar. In a nutshell, the Maya calendar is written in—surprise!—bizarre rectangles. It’s designed to restart every 18,980 days, perhaps because the Maya found a better use for their time than creating a 18,981st bizarre rectangle.

Problem: after 18,980 days, or about 50 years, the entire calendar started over, making it impossible for the Maya to record long-term history. Solution: Maya mathematicians invented a long-count calendar using an extremely convoluted base-20 numerical formula intricately designed to make sure that they’d be dead at least a few millennia by the time they had to deal with those rectangles again.

So more than anything, Dec. 21 is a rare form of Maya New Year. Nothing to panic about.

But for a while, it wasn’t entirely clear that the world would make it to the winter solstice. If there were any year for the world to end, this was it.

Tim Tebow won a playoff game. A silent film won Best Picture. Hostess folded. Tom Hanks discussed the possibility of a Toy Story 4. The New York Knicks have a better record than the Los Angeles Lakers. Rick Santorum won 11 primaries. A Korean satire became the most popular music video in the history of the Internet. “Here Comes Honey Boo Boo” happened—and America was almost okay with it.

Then again, if a year of blooper reel-caliber pop culture were enough to bring about the Four Horsemen, we should have seen the world end sometime in the 1980s. A more plausible reason for 2012 theories sticking around so long is that people craved a reason to live with a carpe- diem attitude (which, alas, 2012 replaced with a YOLO attitude). If you recall, we had four Apocalypse Days in 2011, several more in 2000, and a couple sprinkled throughout the 1990s. The Romans had Apocalypse Days, as did Christopher Columbus, several popes, and the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

For today’s America, it’s a way to keep things interesting. Once the Cold War ended and the world no longer lay under the looming threat of an imminent nuclear cataclysm, we needed a way to remind ourselves to enjoy life and, equally importantly, keep the survivalists occupied.

Let’s just hope none of us are around for the end of the next Maya calendar cycle in 4773, when there won’t be any Twinkies lying around for the straggling survivors after the world ends again.