Tessa Green ’11

Guest Writer

A group of students is clustered around a giant sandbox that has somehow been transported to their classroom floor, the sort of sandbox that would typically be used for castle construction.

Here, oddly, the children carefully brush away the sand rather than dig.

Unlike most, who, when finding trash in the sand, either leave it be or throw it out, they collect their artifacts in labeled Ziploc bags and chart locations in three dimensions, coordinates they will later use to plot the artifacts’ positions in a fourth dimension, time.

These students miss an entire day of classes for the dig. However, none will have any difficulty making up work.

These children are gifted students at Bedford Middle School.

They have been chosen for this program based on nascent intellectual abilities.

These abilities evince themselves differently in each child.

Some kids learn to read before starting kindergarten or bury their noses in math textbooks for fun. Some sneak literary classics under their third grade desks or devote their spare time to their own stories.

The constant acquisition of knowledge leaves these students ahead of the school curriculum; one study found that gifted students already know 40-50 percent of what is taught—and that’s before the course has even started.

They also learn at a faster rate, finishing classwork with so much spare time that the day becomes a series of tedious waits.

It’s understandable, then, that some become bored as the school days slog on.

I gleaned a list of time-filling activities from interviews with gifted students. They stuff notebooks with doodles, stare at the clock in such as way that six hands appear, play snake on calculators, or perform Beethoven’s 5th with their fingertips on their desks.

One girl went so far as to exercise discreetly, contracting various muscles or doing calf raises, to the point that she would experience muscle soreness. Even so, she couldn’t find enough useless entertainments to fill the long classroom hours.

Others use these wasted hours to learn how to think and work.

Easy schoolwork denies gifted students this opportunity.

Educational leader Carol Ann Tomlinson writes frequently of the need for exactly the right level of difficulty.

She’s found that a too challenging class yields frustrated kids who come to think they can’t learn. One that is too easy yields frustrated kids who come to think that they don’t have to.

Gifted children are unable to find a “just right” degree of difficulty in ordinary elementary and middle school classrooms. They aren’t even finding it in the exceptional elementary and middle school classes of Westport.

Here, the Workshop program provides a couple hours every week to learn. Both interviewed students and teachers textbooks say this does little academic good, and leaves Westport’s brightest students languishing, dreaming of the complexity they crave.

They need challenging classes at a young age.However, it’s a lot harder to put gifted kids into their own classes than it sounds.

For one thing, how does one decide if a child is gifted?

The OLSATs, which identify students for Workshop here, are great for finding precociousness, but don’t show much in the way of passion or complex thinking.

Teacher evaluations can get around the testing issue, but they’re biased, with children misbehaving due to boredom frequently overlooked and racial prejudices showing up far more than they should.

These are but a few of the problems associated with finding gifted kids to put into programs in the first place.

There is also the challenge of finding teachers supportive of gifted kids, training teachers to teach them, finding funds for the classes themselves, working any sort of acceleration into curriculum and school schedules, making groupings fluid enough that borderline students aren’t stuck between too hard and too easy, and doing all of that while keeping insatiable students satisfied and prickly parents pleased.

It is impossible to work through this issue in 700 words here.

It’s absolutely evident that gifted children need some form of added difficulty.

It’s just as evident that getting it to them may possibly be more complex than the complexity these children crave.

However, this doesn’t mean that we should at all give up.

The programs we have, while in need of improvement and extension, are significantly better than nothing.

Recent budget cuts have put them under the bus; after all, if gifted kids are so “smart” already, they shouldn’t need anything else.

Unless we start offering separate, speedier subjects or create smaller classes so that teachers can actually teach to the gifted students in their classrooms, we can’t get rid of what we have.

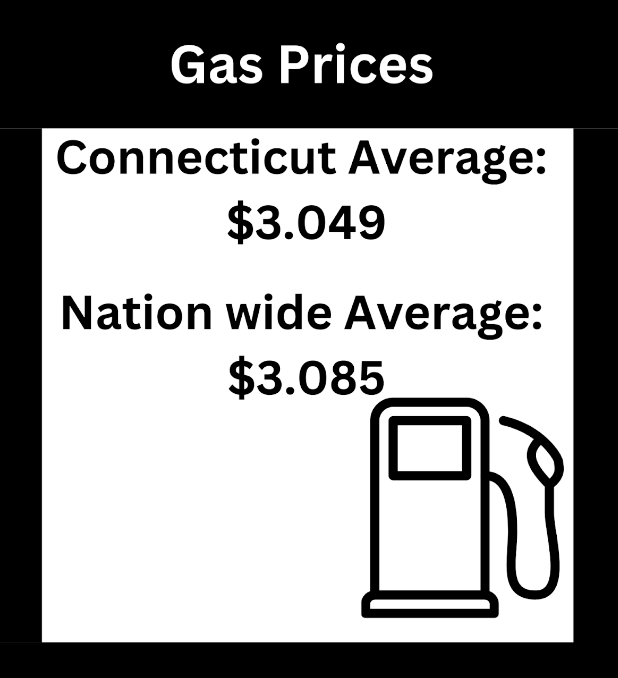

The 411 by the NumbersGifted Education |

6 The estimated percentage of gifted children in the United States (about three million).Source: National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC) |

0 The Federal government dollars are spent directly on gifted education programs.Source: NAGC |

84 Percent of school instruction does not differentiate between gifted and non-gifted students.Source: National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented |

5 Percent of both gifted and non-gifted students who leave school early.Source: Time Magazine |

Aracelis Turkowski • Nov 11, 2011 at 3:52 am

these days. these days say something ideas.

Betty • Mar 30, 2010 at 5:30 pm

Very interesting article. This goes right along with a autobiography I’m reading about growing up as a gifted child. It’s called “I Promised You Daisies” by Robert A. Benjamin. It offers an intimate examination of life through the eyes of an unacknowledged gifted child who has grown up to become an unhappy young adult without understanding how he got that way. I’m really learning a lot.