Trigger warning controversy reaches Staples

On the first day of school, most classes are filled with breezy conversations centered on syllabi and introductions. Students can release the summer air from their lungs while getting readjusted to 6 a.m. mornings with light lectures on various homework policies.

But as English teacher Kim Herzog stepped to the front of her AP Literature class, she didn’t give another speech about the grading system. She gave a warning.

She warned students that the class would be covering sensitive material. For example, that day, they were discussing a rape scene in a book.

A student, whose curiosity must have outweighed their first-day jitters, asked, “Is this our trigger warning?”

Herzog had never heard of the term before.

“I guess so,” she said with a laugh.

Herzog is not alone in being unfamiliar with the phrase. Until recently, trigger warnings only existed in the realm of blogs and online forums.

Back in May, however, the phenomenon of trigger warnings spread throughout college campuses.

According to The New York Times, George Washington University, University of Michigan and Rutgers University are some of the few that found their students petitioning to add trigger warnings to the syllabus. Successful course changes were even implemented by the administration in Oberlin College and University of California, Santa Barbara.

A trigger warning is essentially a warning about any sensitive content that may emotionally affect a student. These often include scenes with violence, rape and drug use. This can potentially “trigger” strong and negative reactions in students, most prominently, in students who have had past experiences with the issues.

The Oberlin College policy towards trigger warnings said, “Realize that all forms of violence are traumatic, and that your students have lives before and outside your classroom, experiences you may not expect or understand.”

As trigger warnings increase in popularity throughout colleges, the conversation is slowly shifting towards high schools as well.

Griffin Haymes ’16, agreeing with the Oberlin College policy, said that trigger warnings are beneficial at the high school level since “you don’t necessarily know if there are people who have been victims in your class.”

Some students have even had experiences where a trigger warning would have been helpful.

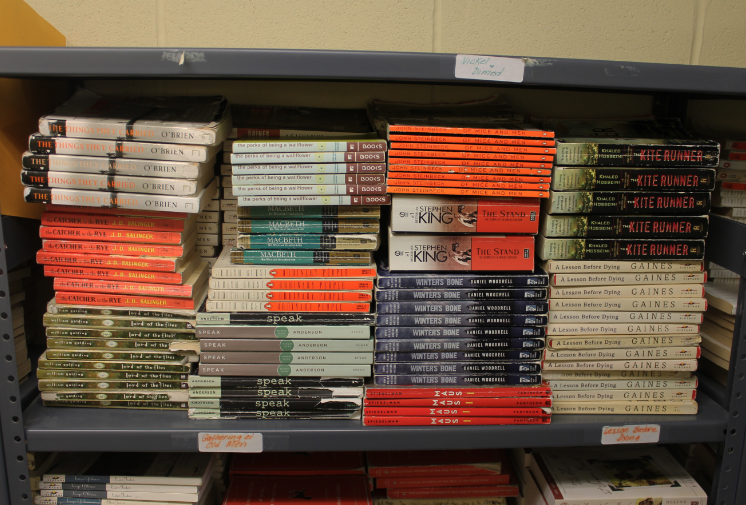

Julie Bilotti ’18 remembers a time last year when her teacher assigned some students to read “The Burn Journals” by Brent Runyon and gave no warning to students about it being violent.

The plot of the book revolves around the main character dousing himself in gasoline and lighting himself on fire. Bilotti said that students “actually ended up switching because they found it so disturbing.”

Sophie Betar ’18 agreed, saying when someone gives you a trigger warning, it makes sure that “you’re prepared to read something inappropriate.”

However, trigger warnings are not without controversy. In fact, when Oberlin College implemented a requirement for trigger warnings in their curriculum, the policy was met with uproar from both the student body and teachers alike. Many claimed that the warnings impeded on freedom of speech, and, as a result, the policy was taken down by April.

Several Staples teachers, while understanding the argument for trigger warnings, agreed that the concept can be flawed.

“You don’t want to ruin the book for the students,” English teacher Brendan Giolitto said. “A lot of shocking things are the point of the book.”

Herzog agreed that trigger warnings can sometimes harm students’ reading of the novel. She pointed out that “it can be important for the students to see how the story unfolds.”

David Raice ’16 agrees with Herzog, feeling that sometimes a warning of what is to come can be detrimental to the impact of the the event.

“I want to be surprised when the thing happens,” he said.

Staples currently does not have a policy for trigger warnings implemented, so it is up to the personal policy of the teachers.

Herzog prefers to warn students with an “overarching statement,” as opposed to giving away specific events in the book.

Giolitto and Herzog both said that they encourage any students who feel uncomfortable to talk to them about potential alternative assignments.

As trigger warnings grow more popular and more controversial, the debate continues to develop.

Teachers grapple with how much they need to protect students, and students struggle with how much they want to be protected.

Carolynn Van Arsdale ’16, a student personally against trigger warnings, said, “In the real world no one’s going to prepare you for those uncomfortable situations. It’s important to experience things like that in class.”