Warrantless searches spark worry

Sirens blare, each passing second a collision with your eardrum. A red light, then blue, then red again. You try to recall what TAG had taught you as you sat in health class; your hands tremble now. The police have arrived. While your brain’s probably crammed with a number of thoughts, one in particular should be considered – what will they do with my cell phone?

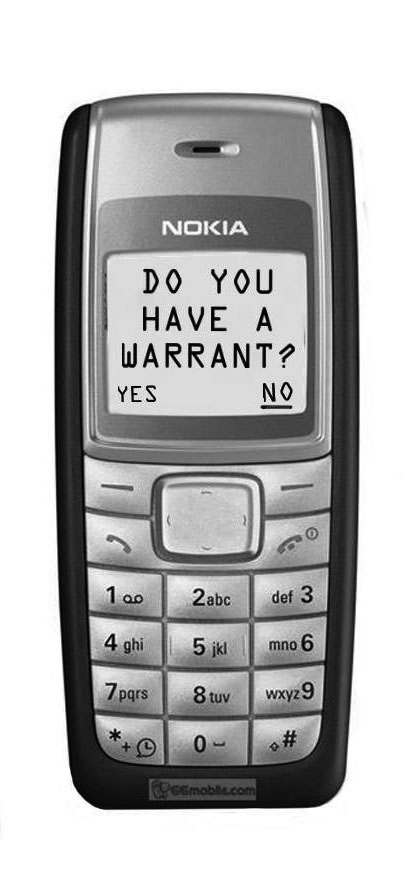

In the absence of a precedent governing phone searches and seizures, police officers in Connecticut do have the right to take your phone and search it, according to Officer Batlin of the Westport Police Department. The resounding response to this? “There’s no way that’s legal,” Nick Ribolla ‘16 said, shaking his head as he paused in the crowded hallway.

Yet phone searches have become an increasingly common tactic used by state police officers. Last year police in Weston confiscated and searched the phones of the high school soccer team while investigating a series of nude photos, Tyler Dyment ‘16, a student there, said.

“They took my phone and started searching around,” Dyment said. “It was pretty awkward, but I got through it.”

Police in Westport are searching phones, too, although, their policy is only to seize cell phones in cases where there is reason to believe that evidence resides on the phones, according to Officer Batlin. No warrant is required, however.

“Some examples of cases where phones have been seized were narcotics-related incidents, harassment, cyber bullying, child pornography and threatening,” Batlin said.

While Officer Batlin insists that students have nothing to worry about unless they are doing something illegal, Alex Uman ‘16 is not convinced. Who’s to say what constitutes the type of cyber bullying or threats that are phone seizing worthy and which are not, Uman argues.

“I think it’s crazy that it’s basically an arbitrary process,” Uman said. “Discretion’s left totally up to the police.”

Other students, like Isabel Perry ‘15, aren’t concerned with the current law. Perry argues that just because officers can search your phone, it doesn’t mean they will.

“Maybe I prefer to see the world through rose-colored glasses,” Perry said, “but I think that the police genuinely have the best interest of teens at heart.”

To Perry’s point, the number of times where police have overstepped their authority is currently unclear. Michael Corsello, a defense attorney based in Norwalk, said that while the topic is certainly hot, he hasn’t witnessed any real problems so far.

“If we do end up calling the department, their typical reaction is, ‘oops we’re sorry about that, sir’” Corsello said, chuckling slightly.

Things could change, though. Later this year, the Supreme Court will rule on two cases regarding cell phone searches, possibly establishing a precedent that alters the current framework.

For now, students will just have to live with the possibility of their phones, treasure troves of teenage texts, being looked through by the police. This brings up an interesting question — if sirens do end up blaring, which will you clutch tighter? Your license or your iPhone?