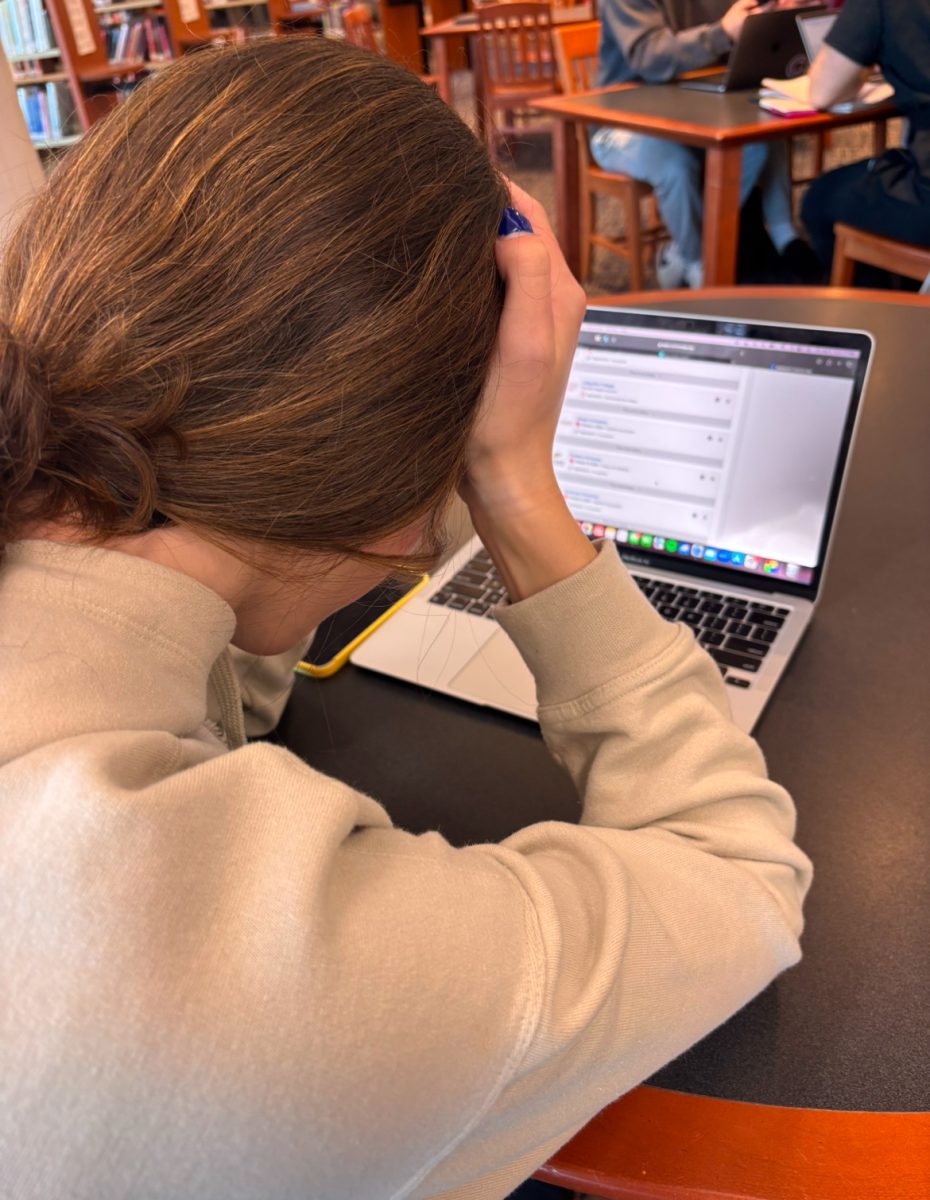

While the physical college application process does not begin until the beginning of senior year, some aspects start much earlier. As the months of May and June roll around, many junior teachers are flooded with one question from their junior students: will they write a letter of recommendation for college?

Prior to posing this question to teachers, students are faced with many questions of their own. What teacher will write the best recommendation?

When Kathryn Lieder ’14 was going through this process last spring, her guidance counselor suggested that she ask either a math or science teacher and also an English or social studies teacher, to balance her application. While this advice was very helpful, it was not the only factor that Lieder considered; she asked the teachers who she thought knew her best.

“I think it’s important to not choose a certain teacher just because you did well in his or her class, but instead to choose a teacher of a class that you truly enjoyed, put a lot of effort into, and showed improvement in throughout the year,” Lieder explained.

Many colleges agree with the approach that Lieder used to make her decision. According to the Vanderbilt University website regarding admissions, the university looks to a teacher recommendation to “humanize you and to tell us something we can’t find out through your transcripts and test scores.”

However, once an eager junior drops the question, it is up to the teacher to decide whether to write the recommendation or not. It’s not a required part of a teacher’s job but a favor to students, teachers said.

And before teachers agree, many require that students sign a waiver that precludes the student from seeing the recommendation. Teachers said they want to relay their honest opinion in confidentiality.

It’s the same concept that drives the signed, sealed envelopes that universities use to send official transcripts, English teacher Alex Miller said. He explained that it guarantees that the document can’t be modified and that no one other than the intended recipient has access to it.

For teachers, recommendations are time-consuming and sometimes stressful. English teacher Liz Olbrych ground out 15 college recommendations this year, for example. She said she made sure to say something positive about each student and precisely capture their personality.

“[I looked at] highlights from the class, like what were some really strong pieces of work they did, as well as what contributions were made to class discussions and group projects,” Olbrych said.

Similarly, math teacher Bill Walsh, who can’t put a number on how many recommendations he has written, says that when he is writing these letters, not only does he consider how rigorous the course is, but also the student’s relationships with other classmates. Walsh likes to describe how the student acts on campus interacting with others based on group work and communication with other students in the class.

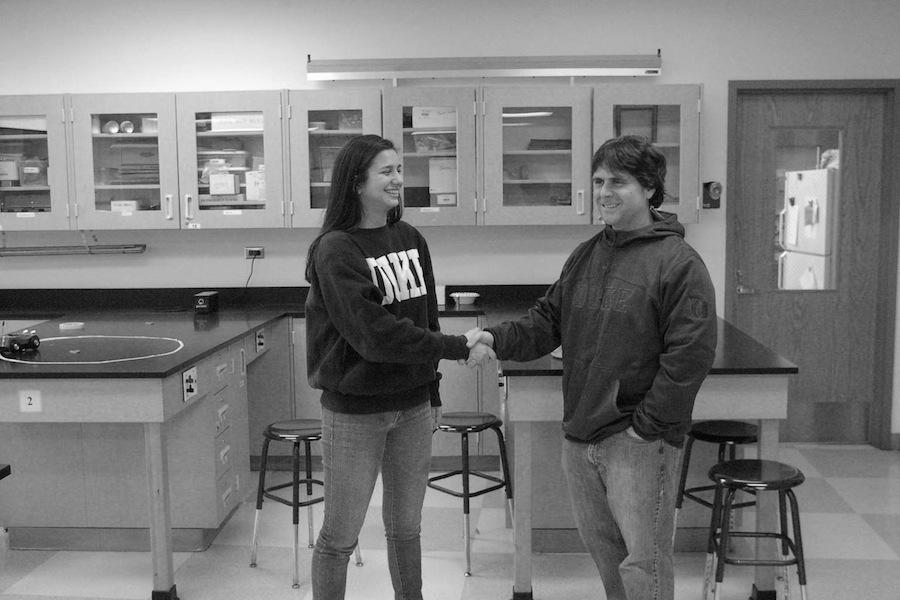

However, Walsh has a very specific approach to the recommendation process. Before beginning to write the recommendation, Walsh said around June of the student’s junior year, he sits down with each student and reaches what he calls “mutual understanding.” This means both Walsh and the student understand the overarching ideas that Walsh may touch upon in the letter.

“If I don’t think I can portray them in a favorable light, I let them know,” Walsh said.

Similar to Walsh, Miller said that he makes it clear that the “letter will accurately reflect their performance in my course.” While he has never said no to a student, many times after students are reminded of their performance in Miller’s class, they decided to make arrangements with other teachers for the recommendation.

While it may seem uncomfortable for teachers to tell students that they can’t write a positive recommendation, students say they appreciate the feedback. All students interviewed unanimously agreed that they would rather have a teacher say no upfront than write a negative recommendation.

“I’ve been working really hard towards getting into college and a negative recommendation would be a big red flag to any college,” Katie Smith ’14 said.

However in the scheme of the rigorous college process, how much would that red flag from the recommendation really affect acceptance?

According to guidance counselor Thomas Brown, there is no formula that tells one how much each component of the college application—essays, test scores, recommendations and more—weigh in to the final decision.

“It’s different for every school,” Brown said.

No matter how much the recommendation is ultimately weighed, Walsh believes that ultimately it’s the work of the student that gets accepted, not the letter of recommendation.

“I believe that [someone] gets into college based on the student [they are]. The college recommendation isn’t the make or break factor,” he said.