The scariest moment of her life happened in the car coming home from a family wedding. Her father had too much to drink, so her mom offered to take the wheel, having only had a couple of glasses of champagne herself. But those couple of glasses made a noticeable difference.

“The car was swerving, and we were going way too fast. She was straddling the line in the middle of two lanes. It really freaked me out because I didn’t know what to say because she’s my mom, but I was terrified the entire time,” she said.

The girl, a senior, who asked to remain anonymous, said that overall her parents have a dangerously cavalier attitude toward drinking and driving.

Although teenagers are often the targets of public service announcements and educational programs concerning risky behavior such as drunk driving, in Westport, at least, it appears to be the adults in the community who are getting behind the wheel while intoxicated.

Of more than a dozen students interviewed, the majority had witnessed an adult drunk driving, and over half said their parents drove drunk regularly.

“Personally, I have never stopped a teenage drunk driver,” Officer Ned Batlin, of the Westport police department said. “It is much more common for the operator to be an adult.”

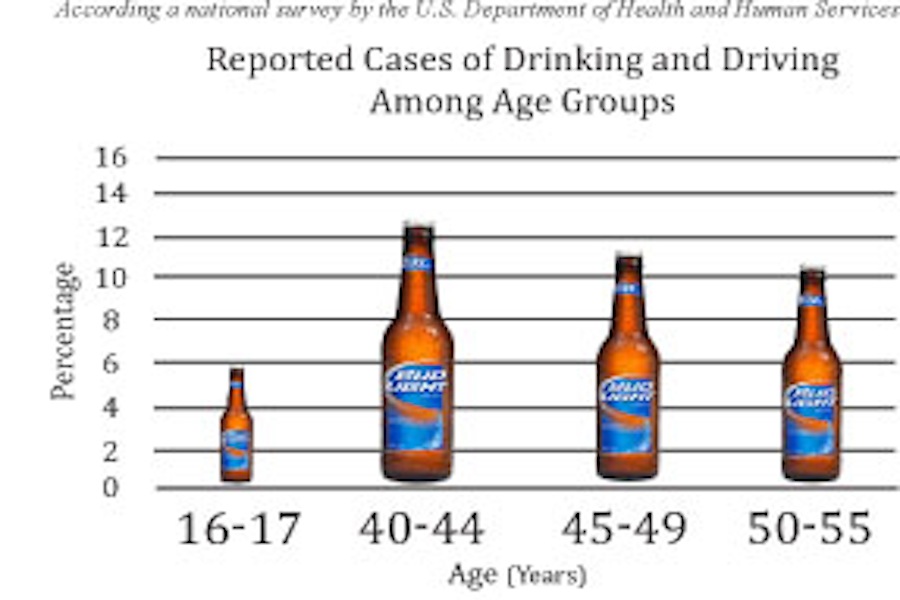

Though Batlin concedes that this may be accounted for by the greater number of adult drivers on the roads in Westport, according to the results of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health conducted by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in 2010 only 5.8 percent of 16-17-year-olds reported driving under the influence of alcohol in the past year.

At the same time, 13.4 percent of persons of ages 40-44, 11.8 percent of people ages 45-49 and 10.5 percent of ages 50-55 reported doing so, all nearly double that of their teenage counterparts.

Some attribute this difference to the result of generations of progress. Westport students have been thoroughly educated about drunk driving by the time they get their licenses. A few generations back this was not the case. Only in the 1960s did research emerge demonstrating the correlation between blood alcohol level and reckless driving, which spearheaded national policy and traffic laws that today seem fundamental.

Even at Staples, Saferides was not started until the 2008-2009 school year, and the Teen Awareness Group (TAG) is currently in its eleventh year.

“You guys have had a better education in the importance of [driving responsibly],” head of SafeRides at Staples Julie Mombello said.

Daisy Laska ’16, a member of TAG, agreed that students are more educated than their parents were, and thus less likely to drink and drive.

“[They] think it’s okay to go out to dinner, have a couple drinks, and drive home,” she said.

One problem, however, is that this scenario is not inherently unlawful.

For those under the age of 21, the legal blood alcohol limit for driving is .02, which would be the equivalent of one drink.

However, for those who can legally drink, the limit is raised to .08, which is high enough that it may not be exceeded even after multiple drinks. Essentially, drinking and driving is illegal for teenagers, but only drunk driving is illegal for adults.

SafeRides executive Will Haskell ’14 said that this ambiguity explains why some adults drink and drive.

“For students, too drunk to drive is defined as having had any alcohol that night,” Haskell said. “It is a clear lines for students. You’ve either had a drink, or you haven’t. That line is less clear with adults.”

Haskell also said that pride might factor into the equation. While in general students are unembarrassed about admitting that they are too drunk to drive, adults may be concerned with the implications of admitting that they shouldn’t get behind the wheel.

Mombello agrees, saying she wishes her generation was more accepting of the need for a designated driver.

“I think that adults in general do not like to admit that they’ve made the mistake of having too much to drink,” Mombello said. “Kids are usually much more willing to admit they need help.”