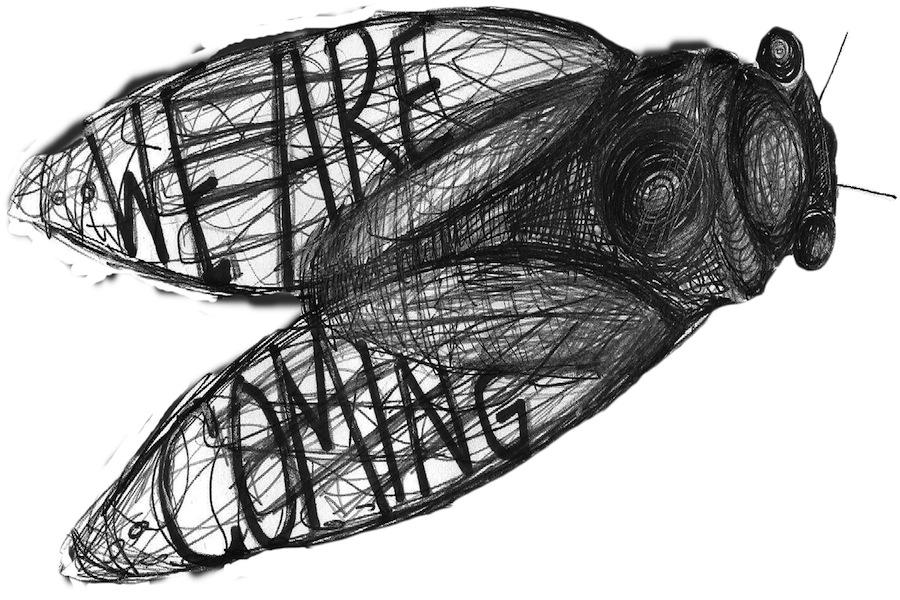

It’s a harsh, mechanical drone, a motorized, whirring soundtrack of summer, a grating advertisement for a mate. It’s the familiar noise of a cicada, but this year, it will be amplified a million-fold.

Dubbed the “bug plague,” “cicadapocalypse” and a “sex invasion” by blogs and news articles, the cicada emergence of Brood II Magicicadas will occur this spring in Connecticut, Maryland, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia. The insect influx will involve from 100,000 to over a million insects per acre, according to John Cooley, a cicada researcher at the University of Connecticut.

The occurrence, which Connecticut entomologist and agricultural scientist Chris Maier described as a “biological phenomenon,” will commence when soil temperatures are warm enough, forecasted for the end of May or the beginning of June. The cicadas will survive for roughly two to three weeks and will be concentrated in areas of central Connecticut, close to traprock ridges and rocky slopes. “They’ll be very numerous in certain hotspots,” Maier said. “In what’s known as a mating aggregation, certain trees can have 10 to 20 thousand.”

The cicadas, winged, red-eyed insects of about 1.5 inches, have spent almost the past 17 years underground, feeding on xylem from plant roots. After this lengthy, subterranean puberty, the cicada nymphs will emerge, crawling from below ground to molt into full-fledged, winged adults. The insects reproduce, then perish, having laid their eggs on plants and trees. The immature cicadas that hatch then sink back into the depths, invisible and silent for the next 17 years.

Although almost two decades have passed since the last emergence, some still remember past cicada events. “I remember all the noise,” math teacher Lenny Klein said. “It sounded like it was from a sci-fi movie, a screeching and buzzing that would fade away.” Klein remembered finding cicada carcasses smashed on the ground during the period of the emergence.

Haley Randich ’14 remembers a 2007 occurrence from a trip to Illinois. “It was horrifying because there were giant, prehistoric-looking bugs everywhere,” Randich said. “When they landed on you–which they did–they made a shrill scream.”

The very suggestion of a cicada mating call is enough to worry many students. “I’ve seen pictures of the cicadas; they’re really scary,” Lexi Lubin ’14 said. “I probably won’t go outside for the time they’re here.”

“I’m so annoyed,” Vidur Nair ’14 said. “I won’t be able to sleep because of all of those stupid crickets chirping.”

Olivia Daytz ’16 also harbored hostility towards the insects. “If there was a cicada in my house, I’d flush it down the toilet,” she said.

Gabi Duncan ’15 had a slightly more optimistic perspective. “It seems kind of cool because I’ve never really seen cicadas before,” Duncan said. “I think the emergence is going to be interesting on the first day that they come out, and, then, after, it’s just going to be gross.”

Experts encourage a more open mind when it comes to the insects. “Some people are freaking out, which is really counterproductive,” Cooley said. The bugs rarely enter houses, generally staying in trees. Furthermore, cicadas, with a taste only for plant sap, do not bite or sting humans.

Even the plants won’t suffer dire harm, experiencing only some discoloration of the stems and leaves, Wesleyan Biology Professor Michael Singer said. “It’s a temporary syndrome and doesn’t harm the plants in the long run,” Singer said. Cooley suggested wrapping delicate, ornamental or fruit trees but was also unconcerned.

“People shouldn’t try to kill them because they’ll end up using so much insecticide,” Cooley said. “I also tend not to eat them because some literature suggests they are mercury bile accumulators.”

“They’re just out there doing their thing. They don’t sting or bite, and they’re not a threat,” Singer added.

Math teacher William Walsh didn’t see the upcoming influx as something to worry about. “I kind of like the sound they make,” he said.

Klein also had a more passive attitude towards the cicadas. “If it happens, it happens,” Klein said. “I’ll be interested to see how my kids react.”

Nevertheless, individuals afflicted with cicada-phobia may be in luck. Based on historical data, Maier predicts that the bugs will not be emerging directly in Fairfield County. He projects higher numbers in central Connecticut towns like Meridan, Hamden, and North Branford. However, Singer feels that the occurrence location is less predictable. “It will depend on where the eggs were laid and whether there are trees around that they can live under,” he said.

Only time will tell if the cicada emergence will affect Westport. Some may dread it, but entomologists are looking on with anticipation. “People should sit back and enjoy the emergence,” Cooley said.