The word “arena” conjures an image of ancient warriors battling snarling, ferocious beasts, with adrenaline coursing, the stakes high, and the consequences of losing as threatening as the very opponent in front of them.

Inside the realm of Staples High School, “arena” refers to a different, and yet scarily similar scene, that of one thousand plus students combating master schedules and department heads to make one perfect schedule. But just as the gladiators of olden times fight no more, so too, has Staples adapted a new, computerized form of scheduling over the past couple of years.

“Arena worked when there were no computers,” Principal John Dodig said of the scheduling tradition that saw it’s last year in 2010. “Arena, in a nutshell, was identical to the computer algorithm, but it used humans instead of bits and bites of data,” Dodig added.

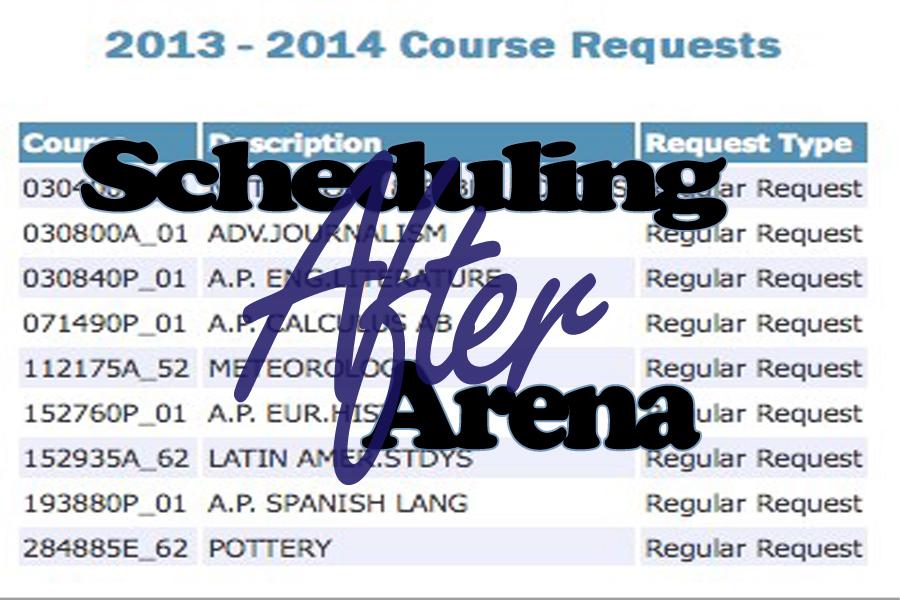

The main difference between arena and the current computer scheduling is student choice. Whereas during arena, students would construct their own schedule choosing the classes they wanted as well as the period numbers and teachers they preferred, computer scheduling gives students all of the classes they want, but assigns them to specific sections as is necessary to meet.

The computer takes into account all course requests, and runs upward of 50,000 possible solutions to ensure every student has all of the classes they want on their schedule. Computer scheduling is also able to even out the number of students in each section, so as to condense the number of teachers and classrooms needed for each course.

Despite this convenience, many students still enjoyed the opportunity to put together their own schedule, and were disappointed with the loss of Arena.

However, Elaine Schawtz, Director of Guidance, states that despite apparent advantages, student choice many times led to frustration and tears.

“Students were trying to do what it takes a computer to do,” Schwartz said. “They would find they had a conflict and they couldn’t resolve it,” she added.

Similarly Susan Pels, a world language teacher, remembers student distress as being the least enjoyable part of arena.

“During arena students were so upset: it was very emotionally traumatic. There were students crying. It was just very chaotic,” Pels said.

According to Dodig, approximately 52% of students left arena each June with outstanding problems with there schedule, to be dealt with at the beginning of the next year, as opposed to the computerized system which leaves every student with a working schedule by the end of the school year.

However, students like Ariel Greene ’13 still lament, somewhat, the loss of choice, especially when it comes to teachers. While Greene says that she has not had a problem with any of her teachers from her computerized schedule, she does think that there are certain advantages lost in the process.

“Getting a teacher [for the second time] is important for upperclassmen especially for college recommendations,” Greene said.

But the ability to choose teachers was also major point of contention during the Arena process. Pels recalls students, while unknowingly begging not to be put into a certain teacher’s class, speaking to that same teacher sitting at the Arena selection table. Furthermore, Dodig calls teacher preferences unfounded, saying students would choose only based on hearsay.

While Dodig admits that some students did walk away from arena with their ideal schedule, both he and Schwartz emphasize that most did not.

“The computer is just so much more fair. Anybody who really needs a particular section can get it, not just people who want it” Schwartz said.

Dodig echoed this sentiment, and while acknowledging the possibly mixed feelings among the student body, felt that the current scheduling system is a vast improvement.

“It’s my job to look at the whole thing,” Dodig said. “[Arena] was just a heck of an awful way to run a school.”