Whether it’s a parent phone call to the Assistant Principal’s office, a hushed referral to a guidance counselor, or a blip on an administrator’s walkie-talkie, an alertness lingers in the wake of Sandy Hook.

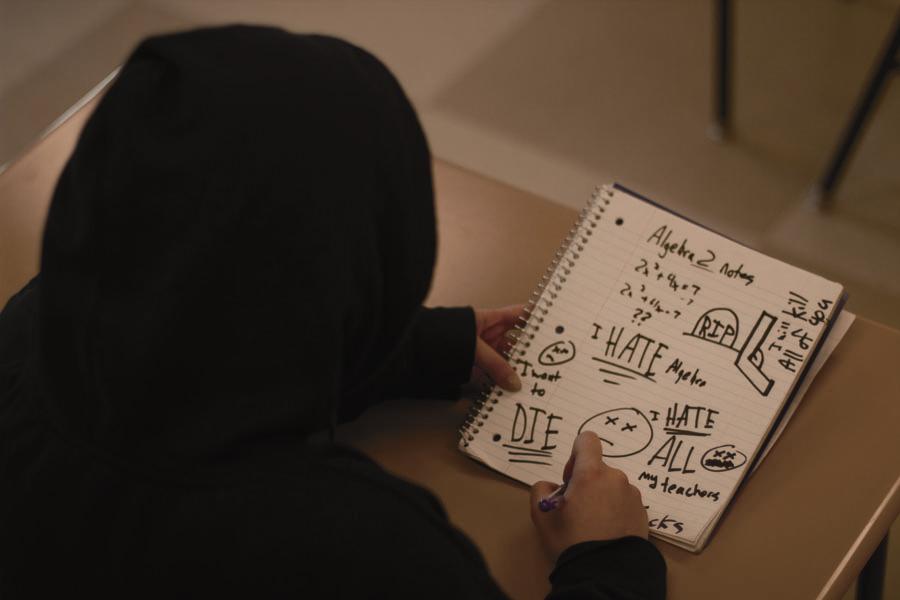

Outside of the classroom, politicians discuss school safety, pointing fingers at gun laws and loopholes. However, a major factor in school safety is mental health: here, the threat may not be a smuggled firearm, but students themselves.

“Kids are more anxious, and staff are more aware,” Assistant Principal Karyn Morgan said. According to Morgan, there have been more referrals to guidance counselors following Sandy Hook. The calls and reports lead to a nuanced procedure to monitor students who may be mentally unstable.

In social worker Sandra Dressler-Berman’s experience, unstable students are more at risk for self-harm than violence against others, although she said the instance of threats has increased due to the availability of online sites like Facebook and Twitter. Still, Berman said that these instances are rare.

But students are alert to the threat posed by their peers. “There was one kid who pretty seriously and consistently joked about bringing a gun to school,” said a student who asked to remain anonymous. According to the student, the teacher and others ignored the comments.

Another student had a similar experience. “Out loud during class, this kid just snapped. He said something along the lines of ‘I will f***ing kill you,’ but everyone in the class ignored it.”

However, neither of the interviewed students felt scared throughout a typical school day. “There isn’t anyone at Staples who I could see genuinely hurting me,” said the first. “It’s just something that you live with,” added the second. “There’s a higher chance that I die in a car crash.”

Noah Schwaeber ’16 said that while he is more watchful of other students post-Sandy Hook, he has never been very suspicious of another student.

“I do feel safe in school because of the kind of district we live in and the way most teachers and students make us feel here,” he said. “However, I don’t think the Sandy Hook shooting should be forgotten, because you never know when an event like this can happen near you, and you need to always look out for something or someone that might cause suspicion.”

Alertness and interaction are key to Staples’s procedure to monitor students who may be unstable.

“We don’t want anyone to be lost in the cracks,” said Director of Guidance Elaine Schwartz. “After Columbine, everyone is more aware of students feeling alone.”

Most basicallyl, students meet individually with guidance counselors regularly and have a grade level assistant principal. “All kids are known by multiple adults,” Principal John Dodig said. Dodig noted recognition given to students through features like student of the month and a breakfast for improved students. “It’s all the little pieces,” he said.

Different organized meetings keep tabs on students with red flags. Within the guidance suite, teams of three guidance counselors, a psychologist, and a social worker meet every other week to discuss students who may have been reported as troubled, usually by a teacher or friend.

Representing another level of screening, administrators, department chairs, and special education teachers convene, along with guidance staff, every Friday morning. Morgan estimated that she raises an average of five names of students she is concerned about at each meeting. “It varies every week,” she said. “Kids may have cut classes or been thrown out of math. It might be kids we have seen frequently or who have been the subject of parent phone calls.”

The Student Study Team (SST), run by Morgan, is another support resource. The group discusses students with social or emotional issues and creates individual plans which may involve dropping down a course level or obtaining social work services.

However, if the situation is one of immediate need, if there is risk of self-harm or outward violence, the student is called in, assessed, and sent home or to a psychiatric facility or hospital. According to social worker Berman, this occurrence is “ not unusual.”

Before re-entry, the student must have a psychiatric evaluation and confirmation of mental stability. Students receive help with make-up work and a script they can use to explain their situation to others.

After identifying students who need help, the school provides services promoting stability and mental health. Troubled students may have arranged meetings with psychologists and social workers. Thomas Vivianno, a psychologist, emphasized the importance of focusing on positive coping skills and open conversation, although the sessions vary case by case.

According to Berman, who meets with many students regularly, social workers may interface with students’ private therapists and also communicate with teachers about how to handle a certain individual.

Teachers play an important role in identifying and monitoring students who need help, all agreed. Teachers are a main source of referrals for the various teams.

Through interaction and class participation, staff gain an insight into students’ overall well-being, with a responsibility to ensure their students’ safety. Staff also are legally obligated to report students who might endanger others or themselves.

A teacher, who asked to remain anonymous in order to protect her student’s identity, taught a suicidal girl in one of her sophomore classes.

“Her friend notified me that this student was having thoughts about hurting herself, and so I had her walk her down to the nurse,” she said. “That was the first time I had to deal with something like this, and I was so concerned. It’s sad when a beautiful, wonderful person wants to hurt themselves.”

Daniel Geraghty, an English teacher, emphasized teachers’ roles as mandatory reporters: if they hear something that may pose a threat to students or faculty, they must report it.

English teachers are cognizant of this obligation as they read over memoirs and poems.

English teacher Heather Colletti-Houde sees these writing assignments as outlets for students who may need support.

“If a student shares an experience or problem through their writing, they are looking for an audience, they are looking for help, and my role is to help those students,” she said.

Colletti-Houde said that even if she knew a student was struggling with a personal problem, she would not tweak the angle of her assignments to be more focused and less open to creativity.

“The beauty and the risk of teaching English are those open conversations and assignments,” she said.

However, English teacher Michael Fulton and Geraghty had a different approach.

“Whenever I assign a more creative piece, I’m nervous,” Fulton said. “I don’t want to have to be the judge between fiction and nonfiction.”

Geraghty felt uneasy especially in light of the Newtown shooting.

“After Sandy Hook I felt very uncomfortable teaching Macbeth. I moved through it quickly and focused less on Macbeth’s motivations,” he said.

Geraghty similarly tries to avoid assignments that may lead students to reveal too much. “My job is not to be a therapist,” Geraghty said. However, he admitted that certain texts lend themselves to more personal writing.

Geraghty has had firsthand experience in acuity for student emotions. He had a concern about a student and discussed this concern with the student, who agreed that he was going through some emotional distress.

“I went to guidance with him and it was taken care of from there,” he said. “And now we have the happy ending–I know this student as a young, successful adult.”