Every year the Staples Boys’ golf team receives 30 dozen brand new golf balls from the town of Westport. They also receive personal golf bags monogrammed with “Staples High School” lettering, as well as home and away t–shirts. They have free tee times at Longshore Golf Course.

Bassick High School in Bridgeport, a school eight miles away from Staples, does not have monogrammed golf bags, nor do they have a football field, a soccer field, a baseball field or a track.

“We have no on–site on-campus anything,” said Bassick varsity head football coach Frank Marcucio. “It’s the parking lot and the school and that’s it.”

The Money:

Money is one resource that always seems to be available in the town of Westport, no matter how bad the financial situation may be. The Board of Education’s battle with budget cuts over past years has not stopped parents from supporting their sons and daughters on the athletic field.

From the $350,000 re–creation of the baseball field last year to the $110,000 addition of the concrete bleachers built into the hill on Loeffler Field, the financial strength of the town of Westport has provided its athletes with some of the best facilities in Connecticut.

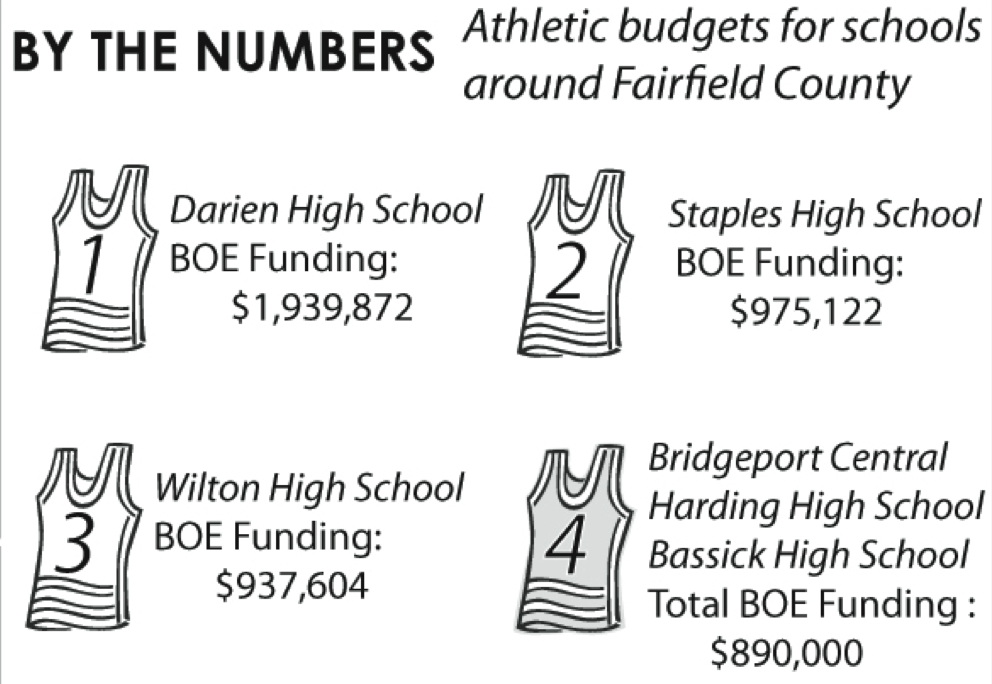

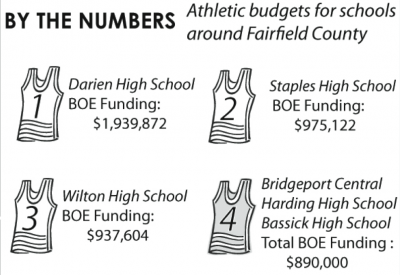

Wealthier towns in Fairfield County spend anywhere from $975,000 given by the Westport Board of Education to Staples to $710,000 in Weston. By contrast, this year all three high schools in Bridgeport shared a total of $890,000.

In addition, wealthier towns also have parent booster clubs that contribute large sums of money. For example, Staples athletic director Marty Lisevick said that the boys’ ice hockey team requires $45,000 worth of ice time each year, but only half is paid by the Board of Education. According to Lisevick, the remainder of the money is raised through advertisement sales, team programs and other fundraising efforts sponsored by the parents.

The football team’s Gridiron Club has paid $130,000 for synthetic turf and another $100,000 over the past five years for locker room improvements, a new scoreboard and a press box. New Canaan High School’s $915,000 athletic budget was supplemented by more than 1 million in donations during the 2008–09 year.

“People have disposable incomes, so people are going to utilize this to enhance their children’s sports abilities,” said New Canaan Athletic Director Jay Egan.

Facilities:

In Bridgeport, tighter money presents challenges. Bassick High School is the only school in the state with no athletic fields on site, which means, for example, that players must walk to and from football practice each day.

“We have to walk three blocks through the hood to walk to the public park. We’re the only high school in the state that has that,” Marcucio said.

Tennis players used to walk to municipal courts nearby before an intermediate school was built, according to Bassick athletic director Peter Shanazu.

The situation is nearly as dire at other schools in financially-strapped areas.

“Talk to any inner–city, it’s basically the same thing,” Marcucio said.

While Staples has enjoyed the renovation of its football, field hockey, and baseball fields in the past five years, Danbury High School has not seen a hole dug or construction workers at the campus in nearly 10 years. Inside the school, the weight room suffers from poor funding.

“Any equipment we get is usually a hand–me–down from a local gym or private party,” said Danbury varsity football coach Dan Donovan.

Equipment and Expenses:

With no place to store its equipment, Bassick High School is at a prime disadvantage compared to other schools in Fairfield County. In fact, the renewal and purchasing of equipment is something that many coaches throughout the FCIAC agonize over each year. For some schools, lack of funding hits hardest here.

“As a football coach I would love to purchase DNA Schutt helmets for our players, but I understand it is not feasible,” said Danbury’s football coach Donovan.

While some of these schools receive funding through grants, the money can often come up short. Last year, for example, Marcucio said that the team used grant money to purchase new uniform jerseys. The team is still waiting for pants.

By contrast, Staples coaches said numerous teams regularly purchase apparel and equipment, and individuals supplement with their own purchases.

By contrast, the issue of equipment is not prevalent for those at Staples. According to girls head tennis coach Casey Devita, each girl on the team has at least two tennis racquets, with costs of $100 or more. Good sneakers and racquets will enhance the game, she added.

Private Instruction:

The advantages of surplus income don’t end with equiptment, coaches and directors said. Devita said she believes that at least 90% of the girls in the tennis program take private lessons. Devita took it one step further by saying that many who are serious tennis players spend in the thousands for gym memberships, tournaments and the court space rental. To Devita, the extra practices show determination to improve and can boost skills greatly.

“If I see a player struggling with a serve one day in practice, it is possible that that night it is fixed, and she comes back the next day serving great. What I am then able to do is go further in strategy because they know the basics,” Devita said.

Private lessons have proven to be an important factor for athletes in wealthier towns, coaches and athletic directors agree.

Staples golf coach Tom Owen said serious golfers on his team spend 25–50 hours with a private swing coach during the off-season; costs can soar into $10,000 range. Consistent regular practice is needed throughout the off-season and weekends at municipal courses and country clubs, memberships at which can run as high as $70,000 plus monthly fees Owen said. Greenwich alone has seven private country clubs and only one municipal golf course to serve over 60,000 residents.

Even at wealthier schools, there are athletes who cannot afford private instruction. A baseball player at Staples who didn’t want to be identified believed that he was the only one trying out for the varsity baseball team this year who hasn’t taken private lessons. The student said he got a job which will allow him to split the cost of the lessons with his parents.

Private lessons represent the biggest disparity between wealthier towns and those strapped for cash, according to Egan. The trend of private lessons in Fairfield County means wealthier kids are training all year round.

“I wonder if there’s anybody on our varsity team who is not involved in private lessons,” said Egan.

While these opportunities to train are readily available in towns like Westport and New Canaan, it is hardly the case in Bridgeport and similar towns. It is a disadvantage for athletes in these towns, said Bassick football coach Marcucio.

“If I had the money I’d do it, too,” said Marcucio. “The kids just don’t have the resources.”

Many students at Danbury High School have jobs after school and cannot take time off from work to travel to a personal trainer or a sports complex even if they could afford it, according to Dan Donovan of Danbury High School. And the money they earn from their jobs goes directly towards buying additional equipment such as uniforms and gloves.

What Really Matters:

While there are vast economic discrepancies among towns in Fairfield County, coaches and athletic directors said it is unclear how much this affects the outcome of an individual team’s success. Bassick head football coach Marcucio described how Bridgeport Central, Bassick and Harding have been state playoff regulars for years in some sports. For example, Marcucio said, inner city kids play basketball on a regular basis because it is available and requires no private lessons.

Bassick athletic director Shanazu agreed that inner city’s schools motto is to do the best they can, to have a positive attitude.

“It’s enjoyable, as long as there’s a ball.”