Connecticut swatting incident highlights growing national problem

Within the last few months, swatting cases have increased countrywide, heightening concern among school communities.

“Lockdown procedures activated. Lockdown procedures activated. An emergency has been reported. Please follow the building lockdown procedures.”

Snapping out of their early morning stupor, students and teachers race into the corners of the classroom, shielding their faces from doors and windows. Confusion and unspoken fear quickly take over the class: is this a drill or is it real?

Similar scenes played out at 17 high schools and two universities throughout Connecticut after calls were received warning of potential gun violence on Friday, Oct. 21. Among them was Staples, forcing the school into lockdown around 9 a.m. As police officers poured onto campus, students and teachers waited: some terrified, some confused. As minutes drew into seemingly endless hours, normal school operations were eventually deemed safe to return to at around 11 a.m, in what would later be characterized as a swatting incident. However, the morning’s unexpected turn left the entire community, administrators included, shaken.

“This one in particular really bothered me because the response warranted an armed response,” Westport Superintendent of Schools Thomas Scarice said. “Last May, we had a shelter in place, which was disturbing, but this one warranted cops going […] room by room with their guns shown.”

Swatting, the practice of calling emergency services on the premise of a false threat, is a growing nationwide epidemic, with a 2019 Anti-Defamation League article citing a 600-case increase from 2011 to 2019. This tactic of harassment wastes resources and instills terror within a community. Some feel that these threats are eerily reminicent of the older trend of bomb threats.

“Bomb threats had the same results,” Scarice said. “Someone would call in a bomb threat and we would have to leave the building. So the disruption is the same, but because of the modern world it’s more gun and school violence related.”

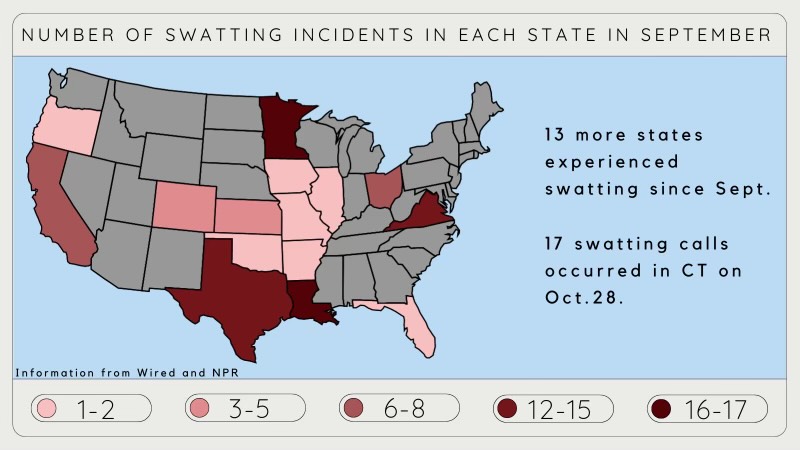

According to a WIRED article, there were 90 swatting calls spanning just three weeks this past September. Often these calls occur after real shooting incidents. The Sandy Hook tragedy that will turn a decade old come December also experienced a similar incident.

“For the years following Sandy Hook, there were [false] calls made in Newtown on or around the anniversary,” Staples Principal Stafford W. Thomas Jr. said. “So unfortunately, we know all too well that [swatting is] here until they find a way to crack down on that.”

As the school year continues to progress, many Staples students have become accustomed to frequent lockdowns.

“It is concerning but in all honesty, I feel as though, to some extent, those lockdowns have simply become a part of being a student,” Jaime Paul ’23 said,“ which in some ways is more concerning as lockdowns should not be the norm for [students].”

Police departments—Westport’s included—are struggling to determine whether these threats are real or fake. Westport Police Department Lieutenant Dave Wolf notes certain indicators may help in determining this, but all calls are taken as real until proven otherwise.

“We always take swatting calls very seriously until we can conclusively determine that the call was in fact a prank,” Wolf said. “We can never know for sure that the call is fake until we get to the school and make sure that there are no issues.”

Meanwhile, for the community most affected by the two-hour lockdown, it is a different feeling of sorts, albeit one becoming all too familiar and frightening.

“Since the last swatting incident I have found myself worried about possibilities of other attacks […] and it’s nerve-racking and scary to have thoughts like these constantly on my mind,” Lily Rimm ’25 said. “I was very distraught after the incident a few weeks ago, and am always alert during the school day in case another incident will occur like this one.”