“It’s now time for the Pledge,” Principal John Dodig announces on the loud speaker.

It’s Wednesday morning and students sit in their classes with fluttering eyelids and cups of caffinated beverages sitting in front of them. While the Pledge is being recited, some students can be seen standing, some sitting, some talking, and some even trying to squeeze in two more minutes of sleep.

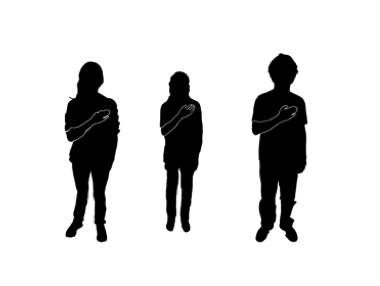

Those who are standing either have their hands on their hearts, their hands behind their backs or their hands at their sides. And one student can be seen peering in from the classroom door, having been caught in the hallway while the Pledge was going on.

This is how the Pledge of Allegiance at Staples plays out. There are 31 words in the Pledge, yet there are so many variations of it that can be witnessed at the school.

Staples started saying the Pledge in 2001, plausibly due to the new sprout of patriotism within the country. However, the question is whether or not the intended patriotism in the school has been achieved.

The fact that nearly half of Staples’ students and faculty don’t recite the Pledge suggests that there are mixed reactions regarding it.

Some students feel that the Pledge is a nice, reflective way to appreciate our country. Kevin Holden ’12 is one of those people. He believes that reciting it is an important facet of the school day. “The Pledge is good. It’s nice to have some patriotism in school,” Holden said.

On the other hand, Maggie Kniffin ’13 thinks that the Pledge is a disappointment. She feels that it should be a moment when the country rewards itself with a little pat on the back, saying that it has done a good job. She believes that the significance of the Pledge has diminished because America has so many more issues to address, such as animal and gay rights.

Suzanne Kammerman, the AP U.S. Government and Politics teacher at Staples, said that it is legally impossible to force a student to recite the Pledge and therefore their allegiance to America. Kammerman does feel that the Pledge should be integrated within the school day.

“The only reason not to [pledge] is because of a political or religious reason,” Kammerman said.

Despite the various opinions on saying the Pledge at Staples, the school must allot a time for students to choose whether or not they say the Pledge.

According to Patrick Doyle, the Educational Program manager for the Conn. chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, the organization feels as though students should not feel compelled or forced to recite the Pledge of Allegiance, and should not feel ridiculed for not reciting it.

Its Origins

The Pledge was written in 1892 by Francis Bellamy, a Christian socialist interested in children’s education. Since then, it has been amended three times with word changes such as “the” replacing “my” in the first line, and “of America” after “the United States.”

In 1952, in the midst of the McCarthy era and the height of the Cold War, the controversial words “under God” were signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. He was inspired to do so after hearing a Washington minister present a sermon about adding those words into the Pledge.

The popularity of the Pledge and the practice of reciting it within schools has waxed and waned throughout the years since it was created.

The Effect of 9/11

In response to the post-9/11 spark of patriotism, Connecticut legislators wanted to enforce saying the Pledge in public schools. On June 7, 2002, Public Act No. 02-119 was passed, which stated that Conn. public schools are required to set aside time that allows students to recite the Pledge. However, the act was not construed to force students to say it.

Now, half the states throughout the country require their students to recite the Pledge.