‘Mrs. America’ reifies relevance of ERA

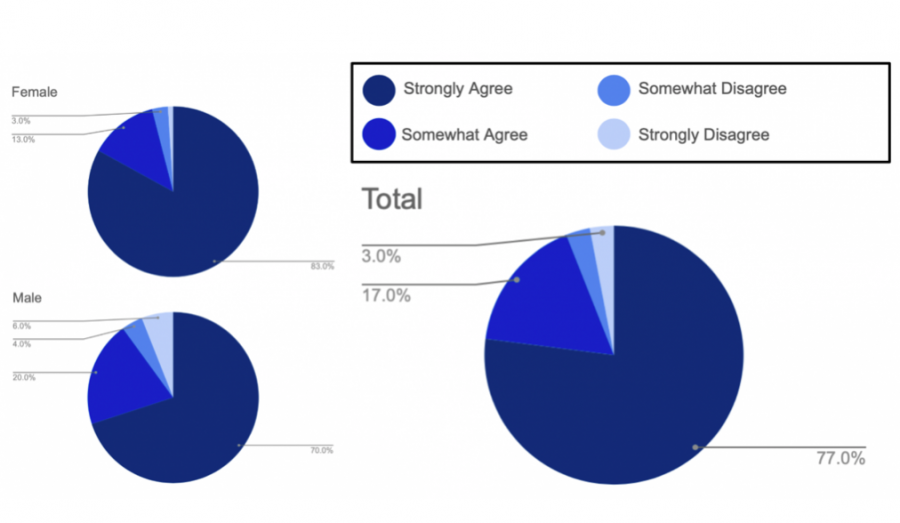

Men and women polled by the ERA Coalition were asked to indicate the degree to which they agreed or disagreed with the statement: “I would support an amendment to the US Constitution that guarantees equal rights for both men and women.” The majority of those surveyed in both groups said they “strongly agree.” All information is courtesy of the ERA Coalition.

For me, “Mrs. America” is a gradually unfurling, forgone tragedy. I already know the ill-fated story of the fall of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). In the margins of a 10th grade notebook, I scribbled annotations on our country’s abiding inability to ensure equality on the basis of sex.

Given a cursory glance, Hulu’s mini-series seems to chronicle a bygone era, evoking a memory of 70’s ambiance with its disco soundtrack, oversized sunglasses and the omnipresence of Virginia Slims cigarettes. While “Mrs. America” offers an obligatory synopsis of history, it also functions successfully as a lesson in the present and positivism for the future.

In nine episodes, the limited series follows eminent feminist revolutionaries—Gloria Steinem (Rose Byrne), Betty Friedan (Tracey Ullman), Shirley Chisholm (Uzo Aduba), Jill Ruckelshaus (Elizabeth Banks) and Bella Abzug (Margo Martindale)—as they champion the passage of the then-27th Amendment. The ERA is remarkably uncomplicated, perhaps to signify the simplicity of its request.

It does not strike the 2020 viewer as contentious, merely asserting all sexes be treated as equal members of society. Yet, in a historical spoiler-alert, the ERA was abandoned for lack of state support—only 35 had ratified it out of the necessary 38.

Initially embraced by a bipartisan coalition and the majority of the public, a vocal and obscurantist group of opponents spearheaded by Phyllis Schlafly (Cate Blanchett) undermined support in the conservative electorate. While “Mrs. America” highlights the work of the women’s “libbers,” the series is at its best when the narrative orbits around the woman responsible for the ERA’s demise: Schlafly.

Though the anti-hero, Schlafly occupies the role of a nuanced villain, simultaneously eliciting our contempt and empathy. At one point, Schlafly affirms, in a meeting with five men, she has “never been discriminated against.” A minute later, she’s asked to take notes for the group because of her “superior [feminine] penmanship.”

Schlafly shouldn’t feel relevant, but her own plight adumbrates that of women irregardless of the decade. Blanchett’s performance demonstrates that while America moves onward, it doesn’t always move forward. As the series illustrates, Schlafly powerfully and effectively thrust herself to the forefront of the male-dominated Republican party and dramatically changed the country’s direction even as she advocated for traditionalism. Under the pretense of preserving the status quo, she constantly sought to disrupt its natural evolution, ultimately proving her ability to marshal social, economic and political forces to her side. Schlafly’s understanding of personal identity politics and political tribalism seems just at home in our current political environment as that of half a century ago.

Therein lies the tragically ironic answer to Schlafly’s subsequent involvement in the STOP ERA movement: it was the only topic through which she could be heard in a sector otherwise dominated by men. “Mrs. America” reminds us that sexual discrimination is not an obsolete concept; rather, it is an unsavory impression long ingrained in our society.

Nearly 100 years after its first introduction, the ERA has still not been enacted. Despite support in state legislatures and 94% of Americans, the ERA faces ardent opposition. According to CNN, the Trump administration requested that a federal court dismiss a lawsuit to add the ERA to the Constitution just last weekend.

However painful, “Mrs. America” offers hope that is intrinsically linked to its villain. I may view the implications of her crusade with abject horror, but I must remember how she achieved it. It’s a welcome takeaway from an arguably weighty series. What one woman could subvert half a century ago, perhaps one can overturn today.