Ross Gordon ’11 & Petey Menz ’11

Managing Editor & Executive Editor

James D’Amico, the 6-12 social studies department coordinator, answered an unexpected phone call from a concerned eighth grade mother five years ago. To the parent and student’s dismay, the student’s middle school teacher recommended that the student take Western Humanities A — the freshman level social studies course.

The incoming ninth grader yearned to be recommended for Western Humanities Honors. So, the student’s mother called D’Amico pleading for him to change the middle school teacher’s recommendation to the harder class — a request D’Amico was not going to approve.

D’Amico told the parent that he would not change the middle school teacher’s recommendation. If the student wanted to take the honors course, he would have to go through the proper override procedures to do so.

“This is his life,” the parent said.

“It’s not his life,” D’Amico said. “It’s freshman social studies.”

While it may just be freshman social studies to D’Amico, some Staples students and their parents see each course and each after school activity as a necessary step closer to an acceptance at a prestigious university.

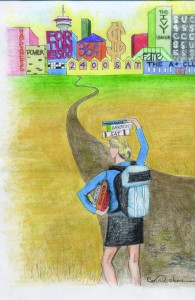

Overrides, heavy course loads with hours of homework and numerous extracurricular activities ultimately lead to a pressure-filled environment for many Staples students. With the recent showings of the documentary “Race to Nowhere,” students, parents and faculty spotted similarities between the film and everyday student life, leading some to believe that Westport students are, in fact, on the marathon race to nowhere.

The Film

“Race to Nowhere,” directed by Vicki Abeles in 2010, suggests that American students may be working too hard for their own good. Many points raised in the film addressed students managing their own personal stresses with their rigorous high school schedules.

The film makes a strong case against stress, asserting that many students across America, including a 13-year-old who committed suicide and a high school student who battled anorexia, have been facing the negative consequences of stress. These examples offer insights into the pressured world that many American students live in, including those at Staples.

In Westport, that pressure comes in several forms. According to parents, many students are stressed out from their workload.

“One day during midterms, my kid was [at Staples] from 6 a.m. to 9:15 at night,” said one mother who wished to remain anonymous to protect the privacy of her child after viewing the documentary on March 8.

As the film documents, guidance counselors and teachers also understand the pressure a rigorous course load curriculum can put on students.

“I do get my share of students who do feel overworked who have taken on more than they imagined,” outreach counselor Chris Lemone said. “They’re bombed with AP classes and they are stressed out.”

However, some students said Staples is only as stressful as the student chooses to make it.

“It’s competitive, but only if that pressure is something important to you,” Rachel Landau ’11 said.

Competition and Pressure

The film touches on many origins for student stress. One such source is parents and the emphasis they put on getting good grades.

“Parents call me up concerned that their kids aren’t getting ‘A’s or ‘B’s and think there must be something wrong,” Lemone said. “I also get kids that come in and feel they don’t live up to parents’ expectations.”

Ultimately, parents are applying this type of pressure so their children will be competitive in the college application process. But well before this process begins, students feel the pressure to succeed in their classes.

“The reality is you need these APs on your transcript to get into an elite college,” said Lis Comm, the 6-12 English department coordinator. “Multiple APs, multiple extracurricular [activities], leadership positions in some of them… If you are set on one of the most selective colleges, you have to have those things.”

According to “Race to Nowhere,” top colleges are not only looking for students to challenge themselves, but also to achieve in them as well. This can lead to students feeling overworked and stressed.

“I don’t think I could have handled this pressure,” social studies teacher Eric Mongirdas said.

Though physics teacher David Scrofani describes himself as a “supporter of kids pushing themselves,” he agreed that there may be too much stress.

“The bad thing about Staples is that there’s no system in place that teaches students moderation or how to know when physical and mental wellbeing is being consumed,” Scrofani said.

When academic pressures overwhelm students, a student’s parents may hire educational tutors.

“There’s a tremendous amount of money spent on private tutoring,” said one parent who wished remain anonymous due to her critical comments of the school system. “I wish there was more learning done at the school.”

Though parents and academic rigor may stress students, one of the largest sources of pressure may be the students themselves.

“My parents don’t pressure me because they know I’m doing it myself,” said Max Samuels ’11.

Samuels, who is currently enrolled in two AP courses, said he rarely finds himself with nothing to do. As the Staples Players president, Samuels frequently acts in shows and practices after school, causing him to start his homework later than other students might. Though busy, Samuels said he would still start his homework at the same time even if he was not participating in Staples Players.

“You just feel like procrastinating much more,” Samuels said.

Jacob Epstein ’12 agreed, saying that he is only up late at night if he puts off completing his work.

“It’s never the school’s fault,” Epstein said.

Where’s the Finish Line?

Though stress may come from a variety of angles, all of them point in the same direction: college admission.

“Kids are concerned that they aren’t going to get into a good college,” Lemone said.

In a place where, over the course of the last three years, 63 students have been sent to Ivy League schools, students may feel abnormal pressure to attend an “elite” university.

“There are 3,700 four-year colleges in America, but it’s the same 200 schools our kids apply to every year,” Principal John Dodig said. “If people are looking for the most competitive colleges, then you can’t avoid the pressure.”

Students agreed that this situation leads to stress.

“Coming from a competitive school like Staples, applying to colleges is more difficult,” Landau said.

PTA council member Marianne Goodell, who played a key role in bringing “Race to Nowhere” to Staples, said the competition for admission into top-ranked colleges has negative impacts on the lives of students.

“I want families and kids to know that there’s more than one way and that there’s kind of a price to pay for trying to fit into that one model that’s not right for everybody,” Goodell said.

Elaine Schwartz, the director of the Staples guidance department, agrees with Goodell’s views on the subject. Schwartz deals with many students and parents who are stressed out because they think that the top-ranked college is the right college.

“We say ‘the right fit’ for colleges all the time,” Schwartz said. “It isn’t always about the name. The best college is the one that is the best fit for the kid.”

Schwartz also said that the college a student attends does not dictate his or her achievement post graduation.

“If you are not going to an Ivy League school, then that doesn’t mean you aren’t going to make it in life,” Schwartz said.

According to guidance counselors and parents, students are stressing over their academic achievement to gain acceptance at top ranked universities. However, if the name of the college is not the ultimate indicator of future success, then students are currently applying pressure for achieving admission to a school that will not matter in the long run.

“If the end is nowhere, then it seems pretty pointless to put yourself through it,” Scrofani said.